Tips for feeding or eating disorders in adults

Who is this for?

These tips have been developed for professionals working across health care; from primary care to hospital general services through to mental health teams and specialist adult eating disorder services.

Introduction

This is the first of four tip sheets to provide you with condensed learning on feeding or eating disorders (FEDs) in adults aged 18 years and over. Tips for working with FEDs in children and young people up to age 18 are available separately here.

FEDs are complex and potentially life-threatening mental health disorders that can affect anyone regardless of age, gender, ethnicity, sex, socioeconomic group or background. There are many myths and misconceptions surrounding FEDs combined with a lack of knowledge. This can produce negative outcomes such as preventing someone from reaching out for help.

This first set of tips is divided into four sections (A-D), and aims to support you in raising your awareness of FEDs and promoting earlier recognition.

Section A: Be aware

Section B: Know the diagnostic categories

Section C: Be aware of what works in treatment

Section D: Understanding the origins of feeding and eating disorders

Section A - Be aware

Stigma and blame are impediments to early detection and good care

Don't be afraid of starting the conversation about people's relationships with food

Be alert, FEDs are easily missed: early intervention leads to better outcomes

- The earlier someone is able to access treatment or support for their FED, the greater chance they have of making a full and sustained recovery.

- Whilst early intervention is important, treatment should also be offered to those who have been unwell with a FED for a long time. Full recovery is possible even after many years of illness

- For adults who are not able to think about full recovery, treatment may facilitate improvements in health and quality of life.

- FED symptoms may be obscured due to apparent social norms e.g. vigorous exercise in someone overweight, restricting certain food types, weight loss in someone who is overweight…look out for compulsive unhealthy or extremes of behaviour including in adults who are not underweight or overweight.

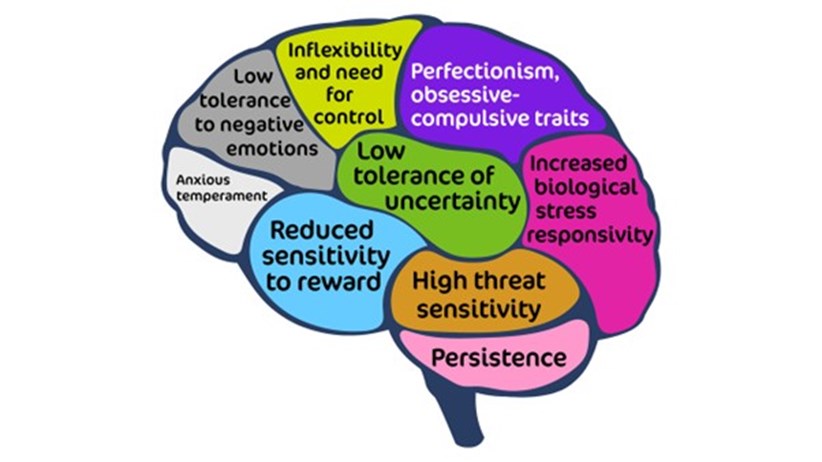

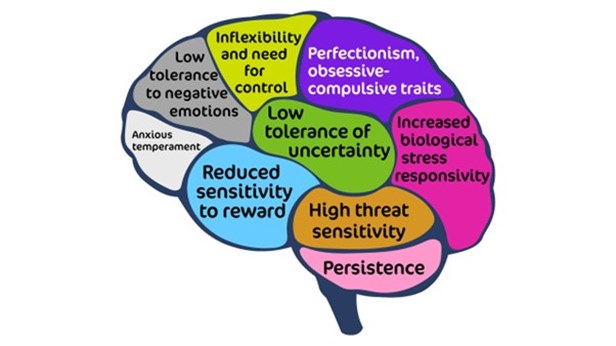

- Look at the slide and think about the risk factors listed that contribute to the development of eating sBeware of outward appearance. It may not always be obvious that someone has a FED, nor does someone have to be underweight to be suffering with a FED.

- While more people with FED are female, many boys and men also have the disorders Because this is not widely appreciated, males tend to be diagnosed later than females and this may reduce their chances of recovery.

- Be alert and know the person may be very unwell, much more so than they may first appear. For example, check their weight and rate of weight loss, their blood pressure and heart rate, their ECG, blood biochemistry, haematology, body temperature and nutritional status. More information is available in tip sheet III on medical investigations.

Remember that feeding or eating disorders (FEDs) are mind-body conditions, care must be holistic to be effective

- Beware of focussing only on the psychological and missing the physical, or vice versa. Effective intervention must include both.

- There is no one single cause; each person will present slightly differently and may not have all the recognised symptoms for one FED. It is also common for FEDs to change over time. They are serious regardless of the specific symptoms being experienced.

- For treatment, you must look at each person as an individual and address both the physical and psychological impact.

Feeding or eating disorders affect all ages, sex, gender, race and ethnic groups

- FEDs may occur at any age, of any ethnicity, gender or background.

- The median age of onset for all FEDs is age 18. Anorexia nervosa (AN) most often emerges in mid-adolescence with a median age of onset of 17 years. Bulimia nervosa (BN) most often emerges in late adolescence with a median age of onset of 18 years. Binge eating disorder (BED) can develop in childhood or adulthood and has a median age of onset of 20 years.

- Onset can occur in later adult years although new onset is relatively rare after age 30

- There is often a delay between onset of a FED and someone seeking help. This means that someone may first seek help for a FED in their 20s, 30s, 40s, 50s or beyond, even if onset was during adolescence.

- In older adults, depressive symptoms or cognitive decline may contribute to under-eating and weight loss that require careful differential assessment from a FED.

- Regardless of age, FED can interrupt relationships, education and work. This can complicate the recovery process during treatment.

Earlier intervention matters: detect and refer early

- Anorexia nervosa significantly reduces quality of life and has one of the highest mortality rates for any mental health disorder.

- Death can result from suicide (20%), heart/cardiac-related events, severe electrolyte imbalance (e.g., low potassium levels), and extreme weight loss.

- Early detection and appropriate care make all the difference.

- Current expert opinion advises that:

- Full recovery is possible;

- The sooner someone gets the treatment they need, the more likely they are to make a fast and sustained recovery;

- A ‘wait and see’ attitude with young people who are developing a FED is not usually helpful;

- The sooner someone with a FED starts an evidence-based NICE-concordant treatment the better the outcome

- First episode Rapid Early intervention for Eating Disorders (FREED) offers an evidence-based early intervention model for emerging adults aged 16 to 25 years with an eating disorder of less than 3 years duration (see www.FREEDfromED.co.uk).

- Be sure you get physical observations (blood pressure, heart rate, temperature), blood biochemistry, haematology and ECG results to ensure rapid and safe clinical decision making for those who are severely restricting food and rapidly losing weight, or who are engaging in multiple daily episodes of vomiting and/or laxative abuse.

- Initially appointments should be weekly and should include weighing of the patient, especially for people who are restricting their food intake (for example in anorexia nervosa and avoidant restrictive food intake disorder [ARFID] , but also sometimes other specified feeding or eating disorders [OSFED] and bulimia nervosa).

Aim to work with the family / carers

- FEDs affect the entire family, therefore family members play an integral role in treatment and should where possible be involved regardless of the patient’s age, although the way they are involved will differ for adults compared to children and adolescents.

- Family and carers are a great resource to support good outcomes, mobilise strengths and build collaboration. Family / carers may include parents, partners, siblings, children, close friends or other important members of someone’s support network.

Positive outcomes can be expected with treatment

- Studies define ‘remission’ and ‘relapse’ in different ways, which can make it difficult to compare treatment outcomes. However, half to two-thirds of adults who start treatment for their FED are likely to experience meaningful reductions in symptoms by the time their treatment ends.

- Better treatment outcomes are predicted by greater symptom change over the early weeks of treatment; it can be helpful to let patients know this, so they can make the most of their early treatment sessions.

- Cross-over from anorexia nervosa to bulimia nervosa is common, as is movement in and out of an ‘other specified feeding or eating disorder’ (OSFED) diagnosis.

- We know less about treatment outcomes for avoidant restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) than the other FEDs – there are no comparable longitudinal studies at this stage.

- Comorbidity with anxiety and/or depressive disorders, trauma symptoms, autism, ADHD and/or personality disorders is common in adults with FEDs. Comorbidities should be considered when planning treatment. This could include adapting FED treatment to take into account other presenting difficulties; adapting treatment for other disorders to take into account the FED; or planning sequential treatment (treating the FED first or vice versa). The PEACE pathway website offers useful guidance on the treatment of FEDs for an autistic person (https://www.peacepathway.org/).

Be aware that people with feeding or eating disorders (FEDs) may lack insight into their condition or be unwilling to talk about their difficulties

- People with anorexia nervosa and other FEDs might have great difficulty in seeing how unwell they are or may be in denial about their illness.

- This can be despite having full clarity of thought and reasoning in their world outside their FED

- It is important to note that many people with FEDs have struggled with disordered eating and distress for many years before seeking help.

- The multidisciplinary team should focus on ensuring that the patient's health and safety come first.

- Specialist eating disorder services are used to working with people who are unsure if they have a problem or are reluctant to think about change.

There are many effects of starvation

Below is a short list, further information is provided in our Tip Sheet 2 What to look out for

- Low mood

- Stress hormones increase - cortisol goes up

- Sexual hormone levels are reduced; amenorrhea is one consequence in females and reduced sexual interest is common in males and females

- Difficulties with concentration and decision making, including focusing on small details, with difficulty seeing the ‘bigger picture’

- Social withdrawal / a reduced interest in socialising

- Physiological effects such as delayed gastric emptying, which means the person feels full quicker, even though the body is malnourished

- Starvation increases the drive to eat in some people, and can trigger food cravings and binge eating behaviour

- A negative cycle can occur with these changes in thinking, feeling, physical experiences and behaviour going on to make the eating disorder worse

- There are multiple other physical effects, including long-term effects like osteopenia (thinning of bones) and osteoporosis; please refer to what to look out for tips

Good quality psychoeducation is important

- Accurate information can help people with FEDs make changes and reduce the distress they experience around eating disorder symptoms.

- Psychoeducation is also important for family members and carers.

- It can be particularly helpful to cover information on starvation effects, as people often don’t realise that low mood, anxiety, social withdrawal and other starvation symptoms are consequences of restrictive eating.

- For people who binge eat, psychoeducation on the ‘vicious cycle’ between restrictive eating and binge eating is important.

- Eating disorders are not all about food; FEDs can be a way of coping with difficult emotions, relationships or life events. People with restrictive FEDs may feel more. anxious/agitated/distressed/guilty before, during and after eating, and less anxious when they don’t eat

- People who binge eat or purge might experience temporary relief from challenging emotions and thoughts when bingeing or purging, but distress and shame may return afterwards.

Section B - Know the diagnostic categories

There are seven specified types of feeding or eating disorders (ICD-11 and DSM-5): be familiar with them so you don’t miss them

- Anorexia nervosa (AN)

- Bulimia nervosa (BN)

- Avoidant restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID)

- Binge eating disorder (BED)

- Rumination-regurgitation disorder (RD)

- Pica

- Other specified feeding or eating disorders (OSFED)

- This includes purging disorder (purging without bingeing). Be aware this can occur in people with type 1 diabetes, when insulin omission is used to influence weight. This is known as Type 1 Diabetes and eating disorders (for more information see resources including MEED guidance)

- It also includes ‘atypical or ‘subthreshold’ AN, BN and BED

- An eighth category in ICD11 is for ‘unspecified feeding or eating disorders’ (UFED)

- For more on each type of disorder see our tips on “What to Look Out For”

One important distinction between different FEDs is whether body image distortion/dissatisfaction is directly linked to the eating disturbance

- Body image distortion/dissatisfaction is a core driver of anorexia nervosa/bulimia nervosa.

- For other FEDS like binge eating disorder and related OSFED presentations, it is sometimes present but not the main issue.

Section C - Be aware of what works in treatment

Our “What to do” tip sheet provides much more detail on interventions

Increase food intake to establish steady gradual weight gain: address starvation as the best first step for anorexia nervosa:

- This may also be required in rumination-regurgitation disorder, ARFID, presentations of OSFED and bulimia nervosa where someone is heavily restricting their food intake and/or has lost a lot of weight.

Bulimia nervosa also has severe physical consequences: regular eating breaks the cycle of bingeing and starving.

Binge eating disorder, avoidant restrictive food intake disorder, regurgitation disorder and pica can also have severe physical consequences. Just different ones.

The best treatment for avoidant restrictive food intake disorder will depend on the specific issues underlying the eating disturbance in the individual; usually a form of cognitive behavioural treatment (CBT) is used.

Weight matters for health, but is a poor measure of health on its own, and differs between people

- Weight and BMI can be important indicators of health but are NOT the only measure of physical risk.

- If possible, consider weight changes as well as current weight. For example, a BMI of 21 may be a cause for concern if someone previously had a BMI of 26 and is now restricting their food intake heavily.

- Use the published guidance on Medical Emergencies in Eating Disorders (2022) to perform a comprehensive assessment of risk.

The illness drives the thinking, it’s not a simple ‘choice’ for the person

- The brain consequences of altered food intake include; increased anxiety and distress when eating and difficulties in making decisions - about food and more generally.

- Increasingly entrenched habits and thinking patterns occur, with more rigid thinking, and reluctance to ‘try new things out’. This can keep people stuck in eating disorder routines.

What do people with FED say they want from professionals?

- I want to receive collaborative, person-centred treatment that is focused on my needs and not just my weight or BMI (body mass index), to help me recover mentally as well as physically.

- I want professionals to show compassion, understanding and trust, while not making assumptions based on my diagnosis.

- Professionals who are working with me will understand how feeding or eating disorders can affect people differently, and how they might get in the way of people accepting help.

- I want people involved in my care to communicate with me and be open and transparent, explaining why certain decisions are made. I want to be able to voice my opinion and to be fully informed throughout my treatment.

- My treatment will always be based on the possibility of recovery and on helping me re- establish who I am, regardless of my past or the length of my illness. People won’t give up on me.

What do carers, relatives and friends of people with FED say they want from professionals ?

- To receive support to help their loved one, regardless of whether their loved one is getting treatment or not.

- For services to understand that carers who are partners, and carers who are parents, may have different needs. Adjust support and the right type, level of information for each group.

- For services to understand the distress we can experience and support us to get help with our own mental and physical health.

Section D - Understand the origins of feeding & eating disorders (FEDS)

Key factors

- some occur long before the onset of a FED, some are close to onset and are triggers, and some maintain the problems once started.

Risk factors

- These can be biological, psychological, social-cultural context and media related, and developmental-neurodevelopmental.

- Predisposing factors: There is a strong genetic component to FEDs, with heritability estimates being in the region of 50-75% for anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN) and avoidant restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID). Estimates for binge eating disorder (BED) are around 40-45%. FEDs show genetic correlations with other psychiatric disorders (particularly anxiety disorders) but also metabolic disorders. Related to this, a family history of eating disorders is a known predisposing factor (likely due to both genetic and environmental effects).

- Other predisposing factors include addiction, mood disorders, diabetes, personality traits (including obsessive-compulsive traits, particularly in AN, and impulsive / emotionally unstable traits, particularly in BN), relationship problems, overvaluation of shape, weight and food, difficulty managing emotions, sport activities like marathon running or ballet, brain changes being identified in studies, having a family member with eating disorder, higher weight, social media, rigidity of thinking (AN), risk avoidance (AN), perfectionism (AN and somewhat BN), low self-esteem (all), general anxiety (all). 50% of people with AN have an anxiety disorder prior to developing AN.

- Triggers: stressful life events and losses - the pandemic appears to be an example, with increased rates of eating disorders after COVID-19. In addition, traumas, including all forms of abuse, food allergies and or coeliac disease, sport activities, other people’s comments about weight or shape, social media, advertising of ‘ideal’ body imagery.

Further Information

Resources

BEAT-HEE-RCPsych

- BEAT Tips Poster

- BEAT leaftlet: Seeking treatment for an eating disorder? The first step is a GP appointment.

- BEAT carers booklet: Eating disorders: a guide for friends and family

- Type 1 diabetes with an eating disorder: more information

- BEAT elearning for nurses (for all ages, not child and young person specific - Each of the 3 sessions will take around 30 to 60 minutes to complete and includes additional learning resources for those looking to further increase their knowledge. To access the elearning in the elfh Hub directly, please visit the links below.

Medical Emergencies in Eating Disorders (MEED)

- Medical Emergencies in Eating Disorders (MEED). Guidance on recognition and management. RCPsych College Report CR233, May 2022. (Replacing MARSIPAN and Junior MARSIPAN)

- Guidance on Recognising and Managing Medical Emergencies in Eating Disorders. Annexe 1: Summary sheets for assessing and managing patients with severe eating disorders. RCPsych College Report CR233, May 2022. (Replacing MARSIPAN and Junior MARSIPAN)

- Medical Emergencies in Eating Disorders. Annexe 2: What our National Survey found about local implementation of MARSIPAN recommendations. RCPsych College Report CR233, May 2022. (Replacing MARSIPAN and Junior MARSIPAN)

- Guidance on Recognising and Managing Medical Emergencies in Eating Disorders. Annexe 3: Type 1 diabetes and eating disorders (TIDE). RCPsych College Report CR233, May 2022. (Replacing MARSIPAN and Junior MARSIPAN)

Other useful resources

From MindEd session Eating Disorders: Further Information for Professionals:

- Talk ED

- Beat (beating eating disorders)

- Centre for Clinical Interventions

- Faculty of Eating Disorders Royal College of Psychiatrists

- F.E.A.S.T. (Families Empowered and Supporting Treatment of Eating Disorders)

- Men Get Eating Disorders Too (MGEDT)

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance for Eating disorders: recognition and treatment

References

- Bulik CM, Coleman JRI, Hardaway JA et al. Genetics and neurobiology of eating disorders. Nat Neurosci, 25, 543-554. doi: 10.1038/s41593-022-01071-z.

- Galmiche M, Déchelotte P, Lambert G, & Tavalacci MP. Prevalence of eating disorders over the 2000-2018 period: a systematic literature review. Am J Clin Nutri, 109, 1402-1413 (2019).

- McClelland, J., Simic, M., Schmidt, U., Koskina, A., & Stewart, C. (2020). Defining and predicting service utilisation in young adulthood following childhood treatment of an eating disorder. BJPsych Open, 6(3), E37

- Neale J, Pais SMA, Nicholls D, Chapman S, Hudson LD. What Are the Effects of Restrictive Eating Disorders on Growth and Puberty and Are Effects Permanent? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.J Adolesc Health. 2019 Nov 23. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.08.032.

- NICE guideline (NG69) 2017. Eating Disorders; recognition and treatments.

- Nicholls D, Becker A. Food for Thought: Bringing Eating Disorders out of the shadows. BJPsych 2019 Jul 26:1-2.

- Petkova H, Ford T, Nicholls D, Stuart R, Livingstone N, Kelly G, Simic M, Eisler I, Gowers S, Macdonald G, Barrett B, Byford S. Incidence of anorexia nervosa in young people in the UK and Ireland: a national surveillance study. BMJ Open 2019; BMJ Open 2019 Oct 22;9(10)

- Smink FRE, van Hoeken D, Hoek HW. Epidemiology, course, and outcome of eating disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry, 26, 543-548 (2013). doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328365a24f.

- Solmi, M., Radua, J., Olivola, M. et al. Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Mol Psychiatry 27, 281–295 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01161-7

- Treasure J, Duarte TA, & Schmidt U. Eating disorders. Lancet, 395, 899-911 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30059-3.

- Vall E & Wade TD. Predictors of treatment outcome in individuals with eating disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Eat Disorders, 48, 946-971. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22411

Further elearning from NHS HEE & MindEd

All ages - NHS HEE TEL Resources

Eating disorders training for health and care staff

This suite of training was developed in response to the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman (PHSO) investigation into avoidable deaths from eating disorders, as outlined in recommendations from the report titled Ignoring the Alarms: How NHS Eating Disorder Services Are Failing Patients(PHSO, 2017).

It is designed to ensure that health and care staff are trained to understand, identify and respond appropriately when faced with a patient with a possible eating disorder. It is the result of collaboration between eating disorder charity Beat and Health Education England with key partners.

Eating disorders training for medical students and foundation doctors

This eating disorders training is designed for medical students and foundation doctors. The two sessions will take around 20-30 minutes to complete and includes additional learning resources for those looking to further increase their knowledge. The sessions also provide good preparation for those who go on to participate in medical simulation training on eating disorders.

Eating disorders training for nurses

This eating disorders training is designed for the nursing workforce. Each of the 3 sessions will take around 30 to 60 minutes to complete and includes additional learning resources for those looking to further increase their knowledge.

Eating disorders training for GPs and Primary care workforce

This eating disorders learning package is designed for GPs and other Primary Care clinicians. The two sessions will take around 30-40 minutes each to complete and includes additional learning resources for those looking to further increase their knowledge.

- GPs and Primary Care: Understanding Eating Disorders

- GPs and Primary Care: Assessing for Eating Disorders

Medical Monitoring in Eating Disorders learning for all healthcare staff who are involved in the physical assessment and monitoring of eating disorders

The eating disorders learning package for Medical Monitoring is designed for primary care teams, eating disorder teams or other teams who are monitoring the physical parameters of a person with an eating disorder. The session will take around 30 minutes to complete and includes additional learning resources for those looking to further increase their knowledge.

Acknowledgements

These tips have been curated, drawn and adapted from a range of existing learning, including MindEd, NHS England, NICE, MEEDs guidance, NHS HEE elfh/BEAT/RCPsych resources. Extracts from the MEEDs are included with permission courtesy of the MEEDs team.

The content has been edited by Dr Karina Allen (MindEd adult eating disorder Editor) and Dr Raphael Kelvin ( NHS England MindEd Consortium Clinical Educator Lead) with close support of the inner expert group of Dr Nikola Kern, Dr Paul Robinson, Dr William Rhys Jones, and Prof Ulrike Schmidt.

We also acknowledge the support and input of our wider expert stakeholder group including BEAT, the MindEd Consortium, and NHS England/Health Education England.

Disclaimer

This document provides general information and discussions about health and related subjects. The information and other content provided in this document, or in any linked materials, are not intended and should not be construed as medical advice, nor is the information a substitute for professional medical expertise or treatment.

If you or any other person has a medical concern, you should consult with your healthcare provider or seek other professional medical treatment. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something that you have read in this document or in any linked materials. If you think you may have an emergency, call an appropriate source of help and support such as your doctor or emergency services immediately.

MindEd is created by a group of organisations and is funded by NHS England, the Department of Health and Social Care and the Department for Education.

© 2023 NHS England, MindEd Programme