Tips for Feeding or Eating Disorders in adults

Who is this for?

These tips have been developed for professionals working across health care; from primary care to hospital general services through to mental health teams and specialist adult eating disorder services.

Introduction

This is the third of four tip sheets to provide you with condensed learning on feeding or eating disorders (FEDs) in adults aged 18 years and over. Tips for working with FEDs in children and young people up to age 18 are available separately here. This tip sheet, focused on what to ask for and what investigations to perform, will be most relevant to GPs and other medical professionals assessing and supporting patients with FEDs.

Early rapid investigation and prompt review of results from investigations are critical, wrapped inside a comprehensive person-centred care plan. Equally important to bear in mind, are the distortions to thinking that the eating disorder can create. Be aware that a very important effect of distorted thinking is lack of insight about the feeding or eating problem. Careful assessment is supported by appropriate medical investigations.

Clinical detection can be challenging. This includes being aware of the secrecy and shame sufferers experience. Be mindful that building trust and rapport will support your assessment. Be alert to hidden aspects of the person’s FED.

Screening questionnaires and tools to help spot and identify feeding or eating disorders (FEDs)

- Warning: do not use screening tools as the sole method to determine whether or not people have a FED.

- Warning: you do not need to be underweight to have an eating disorder, eating disorders can present at any BMI.

- SCOFF assessment:

- Do you make yourself Sick because you feel uncomfortably full?

- Do you worry that you have lost Control over how much you eat?

- Have you recently lost more than One stone (14 lb) in a 3-month period?

- Do you believe yourself to be Fat when others say you are too thin?

- Would you say that Food dominates your life?

- Two or more 'yes' responses indicate a likely eating disorder, although individuals who scores <2 but report other eating disorder symptoms should still be considered for further assessment.

- ABCDE tool for spotting signs of an eating disorder – Family Mental Wealth.

- Physiological parameters - checking against normative ranges table.

- BED questionnaire.

Severely ill and admitted patients

- Use the Medical Emergencies in Eating Disorders (MEED) guidance (2022) to recognise patients at high risk and prevent deaths during treatment of severely ill patients.

Physical investigations to consider in all patients

Many people with FEDs are at high medical risk even at normal or higher weights.

A comprehensive risk assessment should follow the MEED guidelines (2022), and include psychological risk, cardiovascular, nutritional, metabolic and biochemical risks and safeguarding risks.

Body Mass Index (BMI)

- BMI is calculated by dividing weight in kilograms (kg) by height in metres (m) squared: weight (kg) / height (m)2 (or kg / m / m). An online calculator is available at https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/healthy-weight/bmi-calculator/.

- Weight and BMI should not be used as the only indicator of physical health.

- If possible, consider weight changes as well as current weight. Consistent weight loss of ≥0.5kg/week is one marker of concern.

- At a population level, a BMI <18.5 is significantly underweight and may indicate anorexia nervosa (AN) if other diagnostic features are also present. BMI >25 is considered overweight and BMI >30 is considered obese.

- Note that the reference data for BMI are not ethnically sensitive. However, while there is some individual variation, overall there is synergy across countries.

- Clinician judgement is needed to assess and interpret individual BMI relative to familial and population BMI.

- In line with this, MEED (2022) have defined risk in people over the age of 18 as follows:

- Low immediate risk to life: BMI >15 (keeping in mind this is just one marker of risk, and risk may be high based on other physical or nutritional features)

- Medium risk: BMI 13-14.9

- High risk of life-threatening malnutrition: BMI <13

Resources for monitoring cardiac risk

- A sphygmomanometer and appropriate range of cuff sizes; underweight patients may need a child sized cuff while overweight patients will need a large cuff. Inaccurate readings will occur if using cuffs that are too large or too small.

- Note that some patients find blood pressure monitoring intrusive and triggering of ‘body-checking’ thoughts.

- A 12-lead ECG machine.

- Corrected QT interval (QTc) measurement (machine-measurement is 98% accurate).

- A pulse below 50 should prompt an ECG and consideration of review by a cardiologist or specialist eating disorder team.

- Further MindEd resources-learning on ECG interpretation for people working with patients with mental health disorders is available here.

A medical doctor or nurse or other trained professional must check and date the following:

- Weight, height, BMI - consider trends over time

- Restricted food intake, duration

- Restricted fluid intake, duration - look for signs of dehydration

- Amenorrhea in females, duration – ask about oral contraceptive use as these will mask periods

- Binge eating - number of episodes per week

- Self-induced vomiting - number of episodes per week

- Diuretic/diet pills/laxative abuse - type, quantity, number of times per week

- Use of alcohol, tobacco, nicotine, caffeine and recreational drugs; ask about energy drinks and diet soft drinks

- Excessive exercise - hours per day/week

- Distorted body image - describe

- Rapid weight loss -1 kg per week or more

- Heart rate & ECG

- SUSS - impaired squat test (see details under )

- Cardiovascular symptoms like cold peripheries, palpitations, dizziness, fainting, swelling, muscle cramps

- Blood pressure

- Body temperature

- Bloods:

- Full blood count

- Urea and electrolytes

- Liver function tests

- Magnesium

- Calcium profile

- Phosphate

- Glucose (not fasting) -note if low then check ketones (using urine or capillary test strips)

- Thyroid function test

Reasons for blood tests

Adapted from MEEDs guidance with permission

Abnormal electrolytes

- Patients with FEDs can be extremely medically unwell and still have normal blood tests

- Normal electrolytes are therefore not a cause for reassurance

- Abnormal ones are a cause for concern

Abnormal liver tests

- Raised liver enzymes may be caused by:

- Autolysis or self-digestion of hepatocytes, perhaps as a way of releasing energy in a person who is starving

- Hepatic steatosis

- Mild elevation of transaminase levels is common in patients with anorexia nervosa and sometimes appears during the course of refeeding

- Raised alanine aminotransferase (ALT) is common in undernourishment and will usually recover with weight restoration

Abnormal haematological parameters

- Abnormalities in haematological parameters may occur in any person with malnutrition, including those with FEDs, although they will usually resolve with weight restoration and improved nutritional intake

- Changes can involve a number of cell lines, including low white cell counts “leucopenia”, especially neutropenia

- Some low platelet counts, “thrombocytopenia”

- If more than two cell lines are affected, consider other differential diagnoses (e.g. leukaemia)

Self-induced vomiting

- Self-induced vomiting to try to avoid weight gain can occur in AN, bulimia nervosa (BN) and other specified feeding or eating disorders (OSFED) (purging disorder)

- Repeated self-induced vomiting can deplete potassium from the body

- In part by causing alkalosis due to loss of acid from the stomach leading to increased renal potassium excretion

- The resulting hypokalaemia can, if severe, lead to sudden death due to cardiac arrhythmia. ST depression, T-wave inversion and U waves are among the changes observed on ECG

- Some patients will adjust their use of Sando-K potassium supplements to try and hide the effects of vomiting and/or other purging behaviours in blood test results

Laxative abuse

- Taking laxatives to try to avoid weight gain can occur in anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and OSFED (purging disorder)

- The number of tablets taken can escalate, probably because they become less effective

- The subsequent diarrhoea causes loss of electrolytes, resulting in hypokalaemia, hypomagnesaemia and dehydration

- Prolonged laxative abuse can cause colonic atony (loss of muscle function to push contents through) due to progressive weakness of the colonic muscle, and chronic constipation and rectal prolapse can follow, sometimes requiring colectomy

- Laxatives do not result in weight loss, as they do not reduce absorption of calories

- The main consequence of laxative misuse is a loss of bodily fluids and dehydration

- As above, some patients will adjust their use of Sando-K potassium supplements to try and hide the effects of laxative misuse and/or other purging behaviours in blood test results

Diuretic abuse

- In FEDs, diuretics may be used to lower weight, although, as in laxative abuse, the reduction is deceptive as it is due to loss of water from the body

- They cause dehydration and hypokalaemia

- The reduced plasma volume may lead to an elevation in serum aldosterone levels

- Thus, when the diuretics are stopped, the patient can experience severe oedema, which can cause enormous anxiety in the context of intense body image concerns

- Like laxatives, diuretics do not result in weight loss, as they do not reduce absorption of calories

- The main consequence of diuretic misuse is a loss of bodily fluids and dehydration

Thyroid function

- Sick euthyroid syndrome (abnormal thyroid function tests without pre-existing thyroid or pituitary disease) may occur in anorexia nervosa

- Tests will show lowered triiodothyronine levels, low thyroxine levels, and elevated reverse T3

Hypoglycaemia (low blood sugar)

- The average patient with anorexia nervosa who is starving and is severely malnourished, has very limited fat stores. During this time ketones will be produced by beta-oxidation of fats

- In practice most patients with anorexia nervosa are not totally starving and will be carrying enough glycogen to maintain blood glucose

- However, in a totally starving patient who has used up all glycogen and fat stores, fatal hypoglycaemia becomes a possibility

- It is important to check ketones (using urine or finger prick capillary test strips) at the time of hypoglycaemia

- Importantly, ketotic hypoglycaemia should not be treated with rapid-acting carbohydrate (e.g. GlucoGel) but rather with more complex carbohydrates (e.g. food)

- Nonketotic hypoglycaemia is always pathological and rare. It is most commonly seen in insulin overdose, where insulin excess prevents ketogenesis and leads to drowsiness, mood change and stress response (adrenergic symptoms). This is potentially fatal if not appropriately managed

- The co-occurrence of type I diabetes and a FED increases medical risk and requires careful monitoring with input from specialist FED and diabetes teams. Insulin misuse or omission may occur

In bulimia nervosa, and in the binge/purge form of anorexia nervosa and OSFED

- Most biochemical abnormalities are related to purging (i.e. self-induced vomiting and laxative abuse), which can lead to renal impairment

- Hypoglycaemia can also occur, possibly related to binge-related insulin surges

Creatine kinase

- CK is an enzyme contained in muscle cells and released when the muscle is damaged

- In FEDs, the two most common causes of raised CK are muscle autophagy (i.e. the body metabolising muscle as a source of nutrition) and over-exercising, which can result in very high CK levels in undernourished patients who exercise, placing greater burden on the kidneys

Micronutrients

Vitamin deficiencies can give rise to abnormal blood tests, for example:

- Vitamin C deficiency causing anaemia

- Low calcium and phosphate in vitamin D deficiency

Sex hormones

- In specialist services you may also need to check level of sex hormones

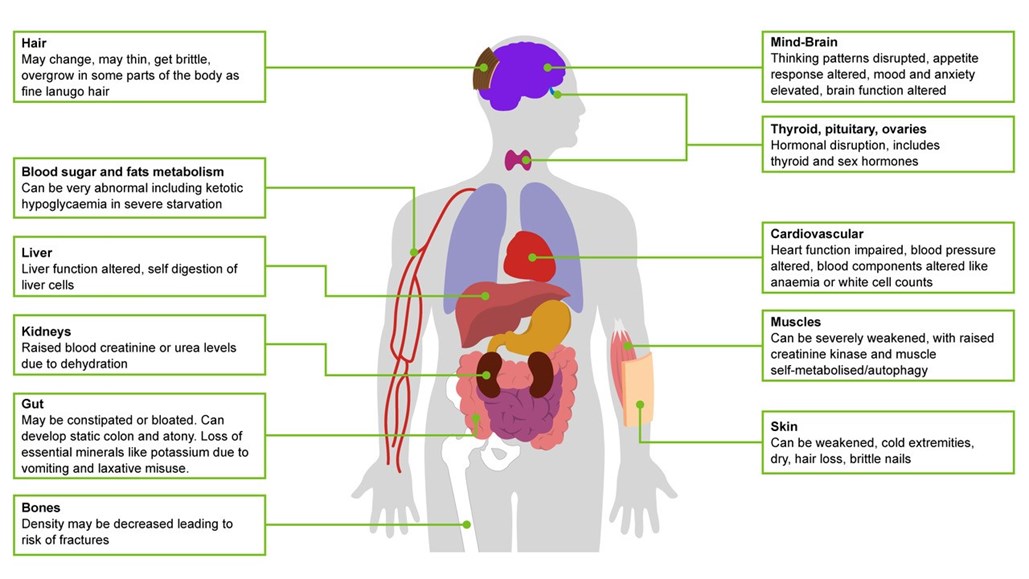

Look out for body symptoms of:

- Dizziness

- Tiredness

- Muscle wasting and weakness

- Low body temperature (core temperature below 35oC)

- Cold hands and feet

- Dry skin

- Hair loss

- Re-emergence of downy unpigmented lanugo “baby” hair on the body

- Feeling faint and actually fainting

Those who are vomiting should be encouraged to:

- have regular dental and medical reviews

- to rinse mouth with fluoride mouthwash after vomiting (a mixture of water and bicarbonate of soda is also effective, or water alone can be used if nothing else is available)

- to wait (at least 15 minutes) before very gently brushing teeth after vomiting

- and to avoid highly acidic foods and drinks

Those who are exercising excessively should be advised of the risks and encouraged to stop exercising if possible; or to reduce exercise or switch to low intensity exercise if unable to stop

- This is best advised after you have established a good initial engagement

- It can be helpful to remind patients that the heart is a muscle, and if other muscles in the body are wasted and under-nourished, the heart may also struggle to tolerate the strain of exercise

Risk of low bone density is present for all who are severely underweight, and particularly in women who are not menstruating

- A bone density scan may be considered for all women with secondary amenorrhea for longer than 12 months

- Seek advice from an endocrinologist regarding optimal management of low bone density

Diabetes mellitus type 1

- Diabetes complicates the management of any eating disorder.

- Insulin or hypoglycaemic drugs may be avoided by the patient to promote weight loss and this can lead to failure of diabetic control.

- In the long term, increased severity of diabetic complications can occur. Psychiatrists and physicians must work closely together in order to optimise outcome in these complex clinical situations. Further information is available on the MEED resource and on the BEAT webpages, links in our resources section below.

Red Flags in Primary Care

(summary courtesy of Medical Emergencies in Eating Disorders 2022 publication - please see MEEDS documents for more detail)

- Patients with FEDs can appear well even when medically very unstable.

- Consult the new Medical Emergencies in Eating Disorders (MEED, 2022) risk assessment framework checklist (see MEED resources; Appendix 3) and use measures most relevant to the patient that you are assessing to decide if the person requires urgent medical admission.

- Anyone with one or more ‘red rating’ (or several Amber ratings-for details please consult the MEED guidelines 2022) should probably be considered high risk, with a low threshold for escalation to a specialist eating disorder service and/or admission to a medical unit.

When you identify multiple red alerts across physical domains, discuss referral to acute medical care

- This may include an emergency admission for medical stabilisation.

- During stabilisation the person will be treated for any severe electrolyte imbalance, dehydration or signs of incipient organ failure.

For patients who need to regain weight in acute settings, staff should have agreed protocols in place for refeeding

Further Information

Resources

BEAT-HEE-RCPsych

- BEAT Tips Poster

- BEAT leaftlet: Seeking treatment for an eating disorder? The first step is a GP appointment.

- BEAT carers booklet: Eating disorders: a guide for friends and family

- Type 1 diabetes with an eating disorder: more information

- BEAT elearning for nurses (for all ages, not child and young person specific - Each of the 3 sessions will take around 30 to 60 minutes to complete and includes additional learning resources for those looking to further increase their knowledge. To access the elearning in the elfh Hub directly, please visit the links below.

Medical Emergencies in Eating Disorders (MEED)

- Medical Emergencies in Eating Disorders (MEED). Guidance on recognition and management. RCPsych College Report CR233, May 2022. (Replacing MARSIPAN and Junior MARSIPAN)

- Guidance on Recognising and Managing Medical Emergencies in Eating Disorders. Annexe 1: Summary sheets for assessing and managing patients with severe eating disorders. RCPsych College Report CR233, May 2022. (Replacing MARSIPAN and Junior MARSIPAN)

- Medical Emergencies in Eating Disorders. Annexe 2: What our National Survey found about local implementation of MARSIPAN recommendations. RCPsych College Report CR233, May 2022. (Replacing MARSIPAN and Junior MARSIPAN)

- Guidance on Recognising and Managing Medical Emergencies in Eating Disorders. Annexe 3: Type 1 diabetes and eating disorders (TIDE). RCPsych College Report CR233, May 2022. (Replacing MARSIPAN and Junior MARSIPAN)

Other useful resources

From MindEd session Eating Disorders: Further Information for Professionals:

- Talk ED

- Beat (beating eating disorders)

- Centre for Clinical Interventions

- Faculty of Eating Disorders Royal College of Psychiatrists

- F.E.A.S.T. (Families Empowered and Supporting Treatment of Eating Disorders)

- Men Get Eating Disorders Too (MGEDT)

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance for Eating disorders: recognition and treatment

References

- Bulik CM, Coleman JRI, Hardaway JA et al. Genetics and neurobiology of eating disorders. Nat Neurosci, 25, 543-554. doi: 10.1038/s41593-022-01071-z.

- Galmiche M, Déchelotte P, Lambert G, & Tavalacci MP. Prevalence of eating disorders over the 2000-2018 period: a systematic literature review. Am J Clin Nutri, 109, 1402-1413 (2019).

- McClelland, J., Simic, M., Schmidt, U., Koskina, A., & Stewart, C. (2020). Defining and predicting service utilisation in young adulthood following childhood treatment of an eating disorder. BJPsych Open, 6(3), E37

- Neale J, Pais SMA, Nicholls D, Chapman S, Hudson LD. What Are the Effects of Restrictive Eating Disorders on Growth and Puberty and Are Effects Permanent? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.J Adolesc Health. 2019 Nov 23. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.08.032.

- NICE guideline (NG69) 2017. Eating Disorders; recognition and treatments.

- Nicholls D, Becker A. Food for Thought: Bringing Eating Disorders out of the shadows. BJPsych 2019 Jul 26:1-2.

- Petkova H, Ford T, Nicholls D, Stuart R, Livingstone N, Kelly G, Simic M, Eisler I, Gowers S, Macdonald G, Barrett B, Byford S. Incidence of anorexia nervosa in young people in the UK and Ireland: a national surveillance study. BMJ Open 2019; BMJ Open 2019 Oct 22;9(10)

- Smink FRE, van Hoeken D, Hoek HW. Epidemiology, course, and outcome of eating disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry, 26, 543-548 (2013). doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328365a24f.

- Solmi, M., Radua, J., Olivola, M. et al. Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Mol Psychiatry 27, 281–295 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01161-7

- Treasure J, Duarte TA, & Schmidt U. Eating disorders. Lancet, 395, 899-911 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30059-3.

- Vall E & Wade TD. Predictors of treatment outcome in individuals with eating disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Eat Disorders, 48, 946-971. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22411

Further elearning from NHS HEE & MindEd

All ages - NHS HEE TEL Resources

Eating disorders training for health and care staff

This suite of training was developed in response to the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman (PHSO) investigation into avoidable deaths from eating disorders, as outlined in recommendations from the report titled Ignoring the Alarms: How NHS Eating Disorder Services Are Failing Patients(PHSO, 2017).

It is designed to ensure that health and care staff are trained to understand, identify and respond appropriately when faced with a patient with a possible eating disorder. It is the result of collaboration between eating disorder charity Beat and Health Education England with key partners.

Eating disorders training for medical students and foundation doctors

This eating disorders training is designed for medical students and foundation doctors. The two sessions will take around 20-30 minutes to complete and includes additional learning resources for those looking to further increase their knowledge. The sessions also provide good preparation for those who go on to participate in medical simulation training on eating disorders.

Eating disorders training for nurses

This eating disorders training is designed for the nursing workforce. Each of the 3 sessions will take around 30 to 60 minutes to complete and includes additional learning resources for those looking to further increase their knowledge.

Eating disorders training for GPs and Primary care workforce

This eating disorders learning package is designed for GPs and other Primary Care clinicians. The two sessions will take around 30-40 minutes each to complete and includes additional learning resources for those looking to further increase their knowledge.

- GPs and Primary Care: Understanding Eating Disorders

- GPs and Primary Care: Assessing for Eating Disorders

Medical Monitoring in Eating Disorders learning for all healthcare staff who are involved in the physical assessment and monitoring of eating disorders

The eating disorders learning package for Medical Monitoring is designed for primary care teams, eating disorder teams or other teams who are monitoring the physical parameters of a person with an eating disorder. The session will take around 30 minutes to complete and includes additional learning resources for those looking to further increase their knowledge.

Acknowledgements

These tips have been curated, drawn and adapted from a range of existing learning, including MindEd, NHS England, NICE, MEEDs guidance, NHS HEE elfh/BEAT/RCPsych resources. Extracts from the MEEDs are included with permission courtesy of the MEEDs team.

The content has been edited by Dr Karina Allen (MindEd adult eating disorder Editor) and Dr Raphael Kelvin ( NHS England MindEd Consortium Clinical Educator Lead) with close support of the inner expert group of Dr Nikola Kern, Dr Paul Robinson, Dr William Rhys Jones, and Prof Ulrike Schmidt.

We also acknowledge the support and input of our wider expert stakeholder group including BEAT, the MindEd Consortium, and NHS England/Health Education England.

Disclaimer

This document provides general information and discussions about health and related subjects. The information and other content provided in this document, or in any linked materials, are not intended and should not be construed as medical advice, nor is the information a substitute for professional medical expertise or treatment.

If you or any other person has a medical concern, you should consult with your healthcare provider or seek other professional medical treatment. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something that you have read in this document or in any linked materials. If you think you may have an emergency, call an appropriate source of help and support such as your doctor or emergency services immediately.

MindEd is created by a group of organisations and is funded by NHS England, the Department of Health and Social Care and the Department for Education.

© 2023 NHS England, MindEd Programme