Tips for CYP feeding or eating disorders

Who is this for?

These tips have been developed for professionals working across health care; from primary and universal care to hospital, general paediatric services right through into specialist CYPMHS.

Introduction

This is the second of four tip sheets to provide you with quick access learning on feeding or eating disorders in children, and young people. Infants 0-2 years are covered in a fifth, separate tip sheet.

There are markers for eating disorders across mind-body-behaviour-relationship domains so look out for them all. Do not make the mistake of only looking in one domain.

This tip sheet aims to help you spot signs and symptoms and look out for problems early.

Definitions

Purging:

The act of getting rid of food/fluids from your body in order to stop yourself gaining weight, for example by making yourself vomit or by misusing laxatives, diuretics etc.

Binge eating:

A binge is where people eat more OR differently and feel unable to stop or control what they are eating even when not hungry, and to the point of being uncomfortable. Some young people develop binge eating disorder (BED) - a serious condition where people repeatedly eat very large quantities of food without feeling like they’re in control of what they’re doing.

Over-exercising:

Compulsion to do excessive exercise in order to lose or control weight

Eating disorders have one of the highest mortality rates amongst all mental disorders

- Death can be due to suicide (20% rate has been recorded in anorexia nervosa)

- Death can also result from

- arrythmias of the heart/abnormal heart rhythm

- low potassium levels which cause abnormal heart rhythm

- infections that may take hold as a consequence of long-term illness

- severe malnutrition

Same day results + same day clinical decision making is very important

- See our “Tip Sheet 3 What Medical Investigations?” for physical investigations to consider

Who gets feeding or eating disorders?

- Around 1 in 20 adolescent girls have an eating disorder at any one time (4-5%)

- Lifetime prevalence by mid-twenties is 1 in 10 (18% for girls and 2.4% for boys)

- In the UK, adolescent girls have the highest risk with 41% having some form of disordered eating behaviour (fasting, purging or binge eating)

Prevalence for different feeding or eating disorders:

- Prevalence for anorexia nervosa was estimated to 0.5% in teenage girls (ratio of 10:1 girls v boys)

- Bulimia nervosa 1% in teenage girls - 0.2% for boys

- ARFID is more evenly distributed between males and females

- Some groups have been identified as particularly vulnerable to the development of restrictive eating disorders, e.g., autistic young people who may develop ARFID or AN

The mind domain: psychological features of eating disorders to be alert to

- Young people with feeding or eating disorders may not acknowledge or recognise that they have a problem:

- they may be in denial about the fact that they have an eating disorder and will go to great lengths to hide it

- you need to spot it - get help from parents or teachers and use your own clinical observations to alert you

- Behaviours to look out for:

- out-of-control eating and purging

- mealtime conflict or eating alone

- may exercise obsessively, e.g., despite injury or young person will get very upset if prevented from doing it

- complex volatile relationships

- social withdrawal

- may struggle with mixed impulsive and obsessive, anxious and/or perfectionist traits

- Mental anguish: need for control of past, present or anticipated events, stress or traumas which can all be linked to disordered eating behaviours

- Note that in binge eating disorder, overeating is linked with a loss of control and feelings of shame and guilt, but no other compensatory behaviours to lose weight

- ARFID is characterised by eating an insufficient quantity or variety of food, sometimes both, there may be avoidance of certain foods and food groups

- ARFID now covers children and young people who used to be categorised as having any of the following: EDNOS/Atypical ED/Feeding disorder of infancy and early childhood/Selective eating disorder

- Relationships suffer because of eating disorders

- they may be in denial about the fact that they have an eating disorder and will go to great lengths to hide it

Know the seven types of feeding or eating disorders so you can spot them: in each there are mind-body-behaviour-relationship features

- Anorexia nervosa (AN)

- Bulimia nervosa (BN)

- Avoidant restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID)

- Binge eating disorder (BED)

- Rumination-regurgitation disorder (RD)

- Pica

- Other specified feeding or eating disorders (OSFED)

- An eighth category in ICD11 is for ‘Feeding or Eating disorders, Unspecified’ (FEDU)

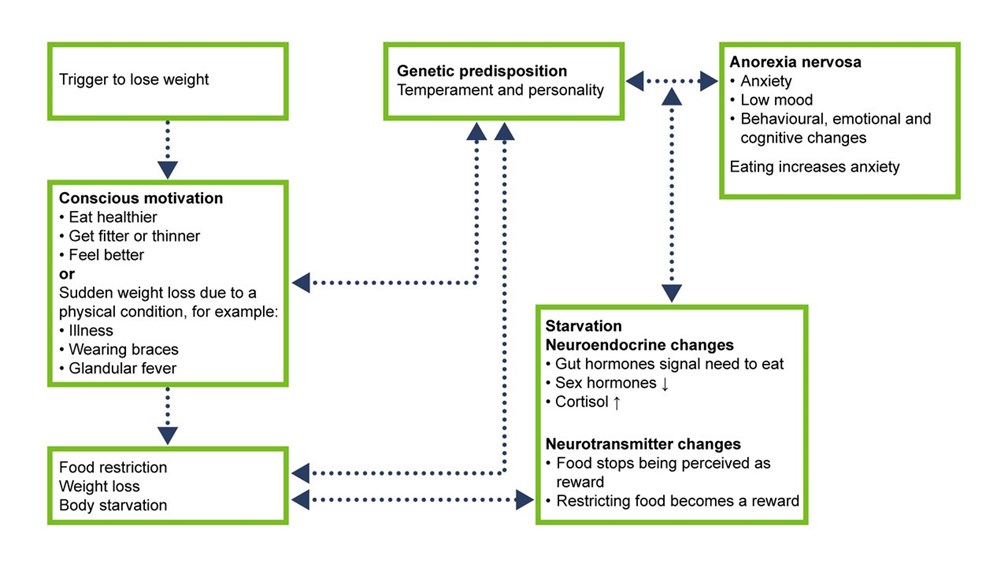

Anorexia nervosa: what to look for

What the young person might think: “all carbs, sugars, fats are unhealthy, and I should not eat them”, “I should count calories and make sure I don’t eat over a certain amount”, “my body is much larger than others see or think”. They may have feelings of needing to be the ‘best’ at something, perfectionism

Where the young person’s body weight might be: weight is low and falling, basic physiology starts to suffer, all body organs impacted - note weight alone is not a reliable indicator. If there is a rapid weight loss, symptoms of starvation may be present even if weight is in a healthy range

How their relationships might be: withdrawing from relationships, anxious, avoiding meals with people, strains in close relationships

What the young person’s behaviour might look like: over exercising, secretive behaviours around eating, perfectionistic traits, obsessive traits like restriction of diet or omitting certain food groups. Excuses such as not feeling hungry or having eaten at school etc.

- AN usually starts in adolescence, around 15-16 years of age (BN 18 and BED 20)

- Suffers from AN have difficulty recognising that they have a problem. Make sure you ask parents or teachers

- Diagnosis:

- Restriction of food intake leads to a significantly low body weight; weight loss is usually present or failure to put weight on while growing

- body weight is below the minimally normal level for their age, sex and height, (BMI between the 5th and 0.3 percentile),

- Alternatively, in children, failure to make expected weight gain or to maintain a normal developmental trajectory

- Intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat, or persistent behaviour that interferes with gaining weight

- Body image distortion, preoccupation or body shape or weight being of paramount importance in terms of self-worth

- There are two subtypes of anorexia nervosa: restricting type and binge eating/ purging type

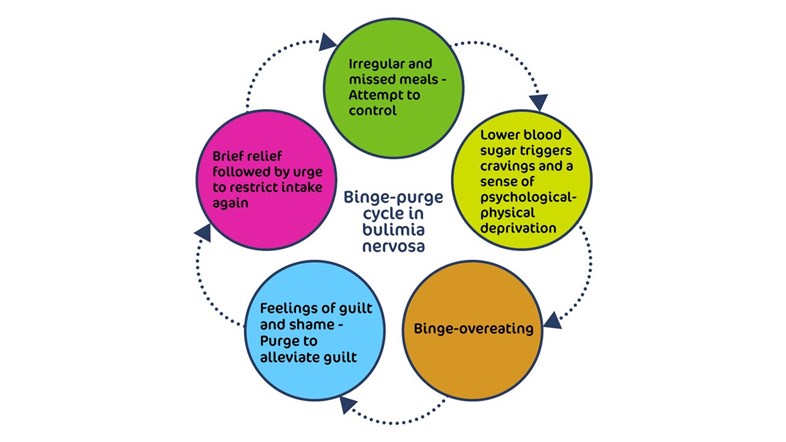

Bulimia nervosa: what to look for

- Recurrent binge-eating followed by compensatory behaviours to avoid weight gain

- Behaviours to look out for: out of control eating and purging, obsessive exercising, complex volatile relationships, may be mixed impulsive and obsessive, secretive eating, avoids eating socially, perfectionist traits

- Diagnosis:

- Episodes of binge-eating:

- Eating, a larger amount of food within a short period of time, even when not hungry

- A lack of control; overeating during the episode

- Inappropriate compensatory behaviour to prevent weight gain (for example, self-induced vomiting, misuse of laxatives, diuretics, intentional insulin omission, use of appetite suppressants like amphetamines, enemas, food restriction, or excessive exercise)

- Binge eating and compensatory behaviours occur at least on average once a week for 3 months

- Weight and shape of paramount importance to self esteem

- Not during episodes of anorexia nervosa

- Episodes of binge-eating:

Look for these physical consequences of bulimia nervosa

- Chronic tiredness

- Dizziness - can be due to altered blood biochemistry, drops in blood pressure on standing

- Tooth decay, loss of enamel and hypersensitivity -due to stomach acid from vomit fluids

- Blood in vomit - due to repetitive microtrauma of the windpipe, rupture of small blood vessels or ulcers

- Scabs on knuckles of index finger - due to sticking finger down the throat

- Two-sided parotid gland enlargements showing as facial shape changes -due to vomiting

- Hair loss, dry itchy skin, growth of new thin hair on the body, brittle nails -due to malnutrition and stress

- Epileptic fits - due to dehydration caused by vomiting and/or purging

- Irregular heartbeat - due to low blood potassium (this can cause cardiac arrest and/or other biochemical changes due to loss of body fluids by purging/vomit)

- Kidney failure - due to dehydration

- Lower bowel problems, bloating, including constipation, loss of normal bowel movements worsens constipation - can become very severe

- Wider gastrointestinal problems - due to dehydration, loss of electrolytes (chloride, calcium, bicarbonate, potassium) which leads to suppression of movement of the intestines (decreased peristalsis)

- Bulimia nervosa can be fatal, as can all the other feeding or eating disorders

Table of some distinguishing features of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder

Binge Eating Disorder: what to look for

- Recurring episodes of excessive food consumption, over a short period of time often to the point of discomfort, accompanied by a sense of loss of control, and feelings of shame and guilt, without vomiting or other purging or other ways of trying to lose weight

- Binges are typically indulgence of ‘forbidden foods’ such as sweets or highly calorific and processed foods

- After a binge, the young person can feel very guilty and ashamed and may try to diet or restrain their eating as a means of compensating for the binge

- Follows a cycle of restriction, thinking about food and feeling deprived, overeating, shame and guilt repeat

- While only a small proportion of those who are overweight have binge eating disorder (BED), about two thirds of young people with BED are overweight or clinically obese

- May have past history of Anorexia Nervosa or Bulimia Nervosa,

- Binge eating may be an attempt to manage emotional distress, which can lead to ‘feeling zoned out’

- This can impact education and work attainment and relationships

- Further traits to look out for: low mood and or anxious, out of control eating, isolated or avoidant in relationships

Avoidant restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID): what to look for

- An umbrella term encompassing a range of presentations previously referred to by multiple descriptive terms (including selective eating, food phobia, food avoidance emotional disorder, functional dysphagia, among others) and typically previously diagnosed as an atypical or not otherwise specified eating disorder, or feeding disorder of infancy or early childhood

- ARFID occurs in children, adolescents and adults and can be associated with low weight, weight in the normal range, or high weight.

- Food intake in ARFID is characterised by insufficient overall quantity, variety, or both, leading to significant negative effects on physical health and/or day-to-day functioning

- Young people with ARFID may miss out on important aspects of social and emotional development due to being unable to eat with others, and family functioning may be severely impacted

- Meals may be small or skipped, or certain foods or food groups avoided

- Look out for nutritional deficiencies and/or calorie imbalances as a result

- In children, there may be faltering growth

- Food avoidance and restriction are not due to a desire to be thinner or perceptions of weight. Nor are bingeing, purging or over-exercising prominent presenting features

- Refusal can be related to heightened sensitivity to aspects of some foods such as texture, smell, appearance, taste, temperature. This is typically exacerbated by anxiety or over arousal

- This is sometimes confused with developmentally normal picky eating, however in ARFID this selectivity is present in a more extreme form leading to nutritional deficiencies and/or associated with significant psychosocial impairment

- Onset may be trigged by a traumatic incident or aversive experience, such as choking, vomiting, abdominal pain, leading to avoidance and extreme caution

- Restricted intake can also be related to low interest in eating or poor recognition of hunger cues

- Limited intake can result from poor internal body awareness and be present in those with high arousal levels (e.g., those with poor emotion regulation as well as those with high distractibility from external stimuli)

- Some groups appear particularly vulnerable to the development of ARFID, i.e., those who are on the autism spectrum, or who have ADHD, anxiety disorders, OCD and a range of medical conditions

Other feeding or eating disorders: what to look for

- Do not fit the exact diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder, rumination-regurgitation disorder, Pica or ARFID, but share some features

- Just as serious as other specified feeding or eating disorders, and in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders - fifth edition (DSM- 5) includes Purging Disorder - misusing laxatives, diuretics, insulin (amongst diabetics) or self-induced vomiting in the absence of binging

- May be the most common group of all eating disorders and can progress from one diagnosis into another. As OSFED is an umbrella term, people diagnosed with it may experience very different symptoms.

Eating difficulties not due to eating disorders

Difficulties with eating can be part of other psychological conditions e.g., phobia of vomiting associated with a fear that certain food can make person sick, loss of appetite in a mood disorder, avoiding eating due to medically unexplained somatic gastrointestinal symptoms. These difficulties are not diagnosed as feeding or eating disorders.

However, if the eating difficulties reach a clinically significant level (e.g., associated with significant weight loss, and other physical consequences of starvation and malnutrition) a feeding and eating diagnosis should be considered

Further Information

Resources

BEAT, HEE, RCPsych

- BEAT Tips Poster

- BEAT leaftlet: Seeking treatment for an eating disorder? The first step is a GP appointment.

- BEAT carers booklet: Eating disorders: a guide for friends and family

- Type 1 diabetes with an eating disorder: more information

- BEAT elearning for nurses (for all ages, not child and young person specific - Each of the 3 sessions will take around 30 to 60 minutes to complete and includes additional learning resources for those looking to further increase their knowledge. To access the elearning in the elfh Hub directly, please visit the links below.

Medical Emergencies in Eating Disorders (MEED)

- Medical Emergencies in Eating Disorders (MEED). Guidance on recognition and management. RCPsych College Report CR233, May 2022. (Replacing MARSIPAN and Junior MARSIPAN)

- Guidance on Recognising and Managing Medical Emergencies in Eating Disorders. Annexe 1: Summary sheets for assessing and managing patients with severe eating disorders. RCPsych College Report CR233, May 2022. (Replacing MARSIPAN and Junior MARSIPAN)

- Medical Emergencies in Eating Disorders. Annexe 2: What our National Survey found about local implementation of MARSIPAN recommendations. RCPsych College Report CR233, May 2022. (Replacing MARSIPAN and Junior MARSIPAN)

- Guidance on Recognising and Managing Medical Emergencies in Eating Disorders. Annexe 3: Type 1 diabetes and eating disorders (TIDE). RCPsych College Report CR233, May 2022. (Replacing MARSIPAN and Junior MARSIPAN)

NHSEI, NICE, NCCMH

- Eating Disorders: Recognition and Treatment NICE Guideline (NG69) 2020

- Access and Waiting Time Standard for Children and Young People with an Eating Disorder: Commissioning Guide, particularly in relation to managing transitions between services 2015

- Eating Disorders Quality Standard (QS175) 2018

- NHS England children and young people’s eating disorders programme 2019

References

- Bould H, De Stavola B, Lewis G, Micali N. Do disordered eating behaviours in girls vary by school characteristics? A UK cohort study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2018; 27: 1473–81.

- Byford S, Petkova H, Stuart R, Nicholls D, Simic M, Ford T, Macdonald G, Gowers S, Roberts S, Barrett B, Kelly J, Kelly G, Livingstone N, Joshi K, Smith H, Eisler I. Alternative community-based models of care for young people with anorexia nervosa: the CostED national surveillance study. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library; 2019.

- House J, Schmidt U, Craig M et al. Comparison of specialist and non-specialist care pathways for adolescents with anorexia nervosa and related eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 2012;45:949-956

- McClelland, J., Simic, M., Schmidt, U., Koskina, A., & Stewart, C. (2020). Defining and predicting service utilisation in young adulthood following childhood treatment of an eating disorder. BJPsych Open, 6(3), E37

- Neale J, Pais SMA, Nicholls D, Chapman S, Hudson LD. What Are the Effects of Restrictive Eating Disorders on Growth and Puberty and Are Effects Permanent? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.J Adolesc Health. 2019 Nov 23. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.08.032.

- NICE guideline (NG69) 2017. Eating Disorders; recognition and treatments.

- Nicholls D, Becker A. Food for Thought: Bringing Eating Disorders out of the shadows. BJPsych 2019 Jul 26:1-2.

- Petkova H, Ford T, Nicholls D, Stuart R, Livingstone N, Kelly G, Simic M, Eisler I, Gowers S, Macdonald G, Barrett B, Byford S. Incidence of anorexia nervosa in young people in the UK and Ireland: a national surveillance study. BMJ Open 2019; BMJ Open 2019 Oct 22;9(10)

- Simic, M., Stewart, C.S., Konstantellou, A. et al. From efficacy to effectiveness: child and adolescent eating disorder treatments in the real world (part 1)—treatment course and outcomes. J Eat Disord 10, 27 (2022)

- Stewart, C.S., Baudinet, J., Munuve, A. et al. From efficacy to effectiveness: child and adolescent eating disorder treatments in the real world (Part 2): 7-year follow-up. J Eat Disord 10, 14 (2022)

Further elearning from NHS HEE & MindEd

Children and Young People - MindEd resources

1) Eating Disorders in Young People

Description: For General Health CYP Entry Level Audience (5-18 yrs)

This session gives an overview of the nature, aetiology and risk factors linked to eating disorders. Also covered are the diagnostic elements that allow us to distinguish between eating disorders and other conditions affecting the eating behaviour of young people.

Author(s):

Dasha Nicholls

2) Eating Disorders; Anorexia and Bulimia

Description: For Specialist Mental Health CYP Health Entry Level Audience (5-18 yrs)

This session is aimed at more experienced/specialist users and outlines the diagnostic criteria and non-specific risk factors for eating disorders that most often start in childhood and adolescence. The eating disorders most frequently seen by mental health professionals, for example, anorexia nervosa, are explained in more detail. Treatment interventions and treatment outcomes for anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa will be discussed, with particular emphasis given to the key family therapy interventions for anorexia nervosa.

Author(s):

Mima Simic

Description: For wider general health audience (0-5 yrs olds)

This session describes the normal developmental progress of children from birth to five; from breast/bottle to eating independently and the difficulties encountered by parents during this developmental process.

Author(s):

Judy More

Description: For Families/parents/carers, Universal Audience (about CYP 5-18 yrs)

This session gives parents basic information and advice about the eating disorders: anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating and similar behaviour, that do not usually meet threshold criteria. It is not intended to address childhood obesity or infant eating difficulties.

Author(s):

Brian Jacobs

Mima Simic

5) Eating Disorders (CT): Families and Professionals

Description: Specialist CYP mental health entry level (5-18 yrs)

This session describes Community Eating Disorder Services for Children and Young people (CEDS-CYP) and the importance of accessing the right support for these disorders early. It explains the physical risks and psychological aspects of eating disorders and the multi-disciplinary nature of CEDS-CYP. It highlights the importance of engaging the young person in treatment and the role of the family in this. The session also outlines psychological and medical treatments, the need to attend to the often co-occurring psychiatric conditions and the use of medication.

Authors:

Mima Simic,

Rachel Bryant-Waugh

6) Eating Disorders (CT): Further Information for Professionals

Description: Specialist CYP mental health entry level (5-18 yrs)

This session will provide a background to Community Eating Disorder Services for Children and Young People (CEDS-CYP) and the assessment and treatment of eating disorders. It will cover psychological treatments, appropriate use of medication and co-occurring conditions.

Authors:

Mima Simic,

Rachel Bryant-Waugh

All ages - NHS HEE TEL Resources

Eating disorders training for health and care staff

This suite of training was developed in response to the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman (PHSO) investigation into avoidable deaths from eating disorders, as outlined in recommendations from the report titled Ignoring the Alarms: How NHS Eating Disorder Services Are Failing Patients(PHSO, 2017).

It is designed to ensure that health and care staff are trained to understand, identify and respond appropriately when faced with a patient with a possible eating disorder. It is the result of collaboration between eating disorder charity Beat and Health Education England with key partners.

Eating disorders training for medical students and foundation doctors

This eating disorders training is designed for medical students and foundation doctors. The two sessions will take around 20-30 minutes to complete and includes additional learning resources for those looking to further increase their knowledge. The sessions also provide good preparation for those who go on to participate in medical simulation training on eating disorders.

Eating disorders training for nurses

This eating disorders training is designed for the nursing workforce. Each of the 3 sessions will take around 30 to 60 minutes to complete and includes additional learning resources for those looking to further increase their knowledge.

Eating disorders training for GPs and Primary care workforce

This eating disorders learning package is designed for GPs and other Primary Care clinicians. The two sessions will take around 30-40 minutes each to complete and includes additional learning resources for those looking to further increase their knowledge.

- GPs and Primary Care: Understanding Eating Disorders

- GPs and Primary Care: Assessing for Eating Disorders

Medical Monitoring in Eating Disorders learning for all healthcare staff who are involved in the physical assessment and monitoring of eating disorders

The eating disorders learning package for Medical Monitoring is designed for primary care teams, eating disorder teams or other teams who are monitoring the physical parameters of a person with an eating disorder. The session will take around 30 minutes to complete and includes additional learning resources for those looking to further increase their knowledge.

Acknowledgements

These tips have been curated, drawn and adapted from a range of existing learning, including MindEd, NHSei, NICE, MMEEDs guidance, NHS HEE elfh/BEAT/RCPsych resources. Extracts from the MMEEDs are included with permission courtesy of the MMEEDs team.

The content has been edited by Dr Mima Simic (MindEd CYP Eating Disorders Editor) and Dr Raphael Kelvin (MindEd Consortium Clinical Lead) with close support of the inner expert group of Prof Ivan Eisler, Dr Dasha Nicholls, Dr Rachel Bryant Waugh and Dr Simon Chapman.

A wider expert reference groups include BEAT (Kathrina Dixon-Ward, Martha Williams, Brooke Sharp), Dr Elaine Lockhart (RCPsych Child and Adolescent Faculty Executive chair), Gemma Trainor (MindEd Consortium RCN lead rep), Prof Ulrike Schmidt (Professor SLAM/KCL and MindEd Editor) Dr Lisa Shostack (MindEd Consortium BPS Lead Rep).

Disclaimer

This document provides general information and discussions about health and related subjects. The information and other content provided in this document, or in any linked materials, are not intended and should not be construed as medical advice, nor is the information a substitute for professional medical expertise or treatment.

If you or any other person has a medical concern, you should consult with your healthcare provider or seek other professional medical treatment. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something that you have read in this document or in any linked materials. If you think you may have an emergency, call an appropriate source of help and support such as your doctor or emergency services immediately.

MindEd is created by a group of organisations and is funded by NHS England, the Department of Health and Social Care and the Department for Education.

© 2023 NHS England, MindEd Programme