Tips for CYP feeding or eating disorders

Who is this for?

These tips have been developed for professionals working across health care; from primary and universal care-hospital general paediatric services right through into specialist CYPMHS.

Introduction

In this, the third of five tip sheets on feeding and eating disorders in children and young people, we provide quick access tips on what to ask for and what investigations to perform. This will be most relevant to GPs and other medical professionals assessing and supporting patients with feeding or eating disorders.

Early rapid investigation and same day review of results of investigations wrapped inside a comprehensive person-centred care plan is critical. Equally important to bear in mind, are the distortions to thinking that the eating disorder can create. Be aware that a very important effect of distorted thinking is lack of insight about the feeding or eating problem. Careful assessment is supported by appropriate medical investigations.

Clinical detection can be challenging. This includes being aware of the secrecy and shame sufferers experience. Be mindful that building trust and rapport will support your assessment. Be alert to hidden aspects of the young person’s feeding or eating disorder.

Screening questionnaires and tools to help spot and identify eating disorders

- Warning: do not use screening tools as the sole method to determine whether or not people have an eating disorder

- Warning: the child or young person does not need to be underweight to have an eating disorder, eating disorders can present at any BMI

- SCOFF assessment

- Physiological parameters - checking against age standardised normative ranges table

- BED questionnaire

Severely ill and admitted patients

- For young people who need to regain weight in acute settings, staff should have agreed protocols in place for refeeding

- Use the Medical Emergencies in Eating Disorders (MEED) guidance (2022) to recognise patients at high risk and prevent deaths during refeeding and inpatient care of severely ill patients

Physical investigations to consider in all patients

Many people with eating disorders are at high medical risk even at normal or higher weights.

A comprehensive risk assessment should follow the MEED guidelines (2022), and include psychological risk, safeguarding risks, cardiovascular, nutritional, metabolic and biochemical risk.

Age adjusted median Body Mass Index (BMI)

- Age-adjusted BMI (median BMI for age and sex; %mBMI) can be calculated by dividing the patient’s BMI by the median BMI for someone of their age and sex

- Median BMI for a given age can be read from BMI centile charts (RCPCH BMI centile charts: Link here), or there are programmes and apps (Junior Marsipan App for median BMI link here) that use the UK BMI reference data.

- Note that the reference data are not ethnically sensitive. However, while there is some individual variation, overall there is synergy across countries (BMJ, 2007 link here)

- Clinician judgement is needed to assess and interpret individual BMI relative to familial and population BMI.

- In line with this, MEED (2022) have defined risk in people under the age of 18 as follows:

- Low immediate risk to life: median BMI >80%

- Medium risk: median BMI 70-80%

- High risk of life-threatening malnutrition: median BMI <70

Resources for monitoring cardiac risk

- A sphygmomanometer and appropriate range of cuff sizes. Note that some patients find this measure intrusive and triggering of ‘body-checking’ thoughts

- A 12-lead ECG machine

- Corrected QT interval (QTc) measurement (machine-measurement is 98% accurate)

- A pulse below 50 should prompt an ECG and consideration of review by a paediatrician

- Further MindEd resources-learning on ECG interpretation for people working with patients with mental health disorders is available here

A medical doctor or nurse must check and record the following:

- Weight, height, % median BMI -Measure height and weight to calculate how the young person’s body weight compares to the weight of other young people of the same age and sex

- Restricted food intake, duration

- Restricted fluid intake, duration - look for signs of dehydration

- Amenorrhea, duration

- Binge eating - number of episodes per week

- Self-induced vomiting - number of episodes per week

- Diuretic/diet pills/laxative abuse - type, quantity, number of times per week

- Excessive exercise - hours per day/week

- Distorted body image - describe

- Rapid weight loss -1 kg per week or more

- Heart rate & ECG

- SUSS - impaired squat test (see details under Red Flags below)

- Cardiovascular symptoms like cold peripheries, palpitations, dizziness, fainting, swelling, muscle cramps

- Blood pressure

- Body temperature

- Bloods:

- Full blood count

- Urea and electrolytes

- Liver function tests

- Magnesium

- Calcium profile

- Phosphate

- Glucose (not fasting) -note if low then check ketones (using urine or capillary test strips)

- Thyroid function test

Reasons for blood tests

Adapted from MEEDs guidance with permission

Abnormal electrolytes

- Patients with eating disorders can be extremely medically unwell and still have normal blood tests

- Normal electrolytes are therefore not a cause for reassurance

- Abnormal ones are a cause for concern

Abnormal liver tests

- Raised liver enzymes may be caused by:

- Autolysis or self-digestion of hepatocytes, perhaps as a way of releasing energy in a person who is starving

- Hepatic steatosis

- Mild elevation of transaminase levels is common in patients with anorexia nervosa and sometimes appears during the course of refeeding

- Raised alanine aminotransferase (ALT) is common in undernourishment and will usually recover with weight restoration

Abnormal haematological parameters

- Abnormalities in haematological parameters may occur in any person with malnutrition, including those with eating disorders, although they will usually resolve with weight restoration and improved nutritional intake

- Changes can involve a number of cell lines, including low white cell counts “leucopoenia”, especially neutropaenia

- Some low platelet counts, “thrombocytopaenia”.

- If more than two cell lines are affected, consider other differential diagnoses (e.g. leukaemia)

Self-induced vomiting

- Repeated self-induced vomiting can deplete potassium from the body

- In part by causing alkalosis due to loss of acid from the stomach leading to increased renal potassium excretion

- The most life-threatening consequence of the resulting hypokalaemia is sudden death due to cardiac arrhythmia. ST depression, T-wave inversion and U waves are among the changes observed on ECG

Laxative abuse

- Taking laxatives to try to avoid weight gain occurs in anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and OSFED (purging disorder)

- The number of tablets taken can escalate, probably because they become less effective

- The subsequent diarrhoea causes loss of electrolytes, resulting in hypokalaemia, hypomagnesaemia and dehydration

- Prolonged laxative abuse can cause colonic atony (loss of muscle function to push contents through) due to progressive weakness of the colonic muscle, and chronic constipation and rectal prolapse can follow, sometimes requiring colectomy

Diuretic abuse

- In eating disorders, diuretics may be used to lower weight, although, as in laxative abuse, the reduction is deceptive as it is due to loss of water from the body

- They cause dehydration and hypokalaemia

- The reduced plasma volume may lead to an elevation in serum aldosterone levels

- Thus, when the diuretics are stopped, the patient can experience severe oedema, which can cause enormous anxiety in the context of intense body image concerns

- Laxatives and diuretics do not result in weight loss, as they do not reduce absorption of calories

- The main consequence of laxative and diuretic misuse is a loss of bodily fluids and dehydration

Thyroid function

- Sick euthyroid syndrome (abnormal thyroid function tests without pre-existing thyroid or pituitary disease) may occur in anorexia nervosa

- Tests will show lowered triiodothyronine levels, low thyroxine levels, and elevated reverse T3

Hypoglycaemia (low blood sugar)

- The average patient with anorexia nervosa who is starving and is severely malnourished, has very limited fat stores. During this time ketones will be produced by beta-oxidation of fats

- In practice most patients with anorexia nervosa are not totally starving and will be carrying enough glycogen to maintain blood glucose

- However, in a totally starving patient who has used up all glycogen and fat stores, fatal hypoglycaemia becomes a possibility

- It is important to check ketones (using urine or capillary test strips) at the time of hypoglycaemia

- Importantly, ketotic hypoglycaemia should not be treated with rapid-acting carbohydrate (e.g. GlucoGel) but rather with more complex carbohydrates (e.g. food)

- Nonketotic hypoglycaemia is always pathological and rare. It is most commonly seen in insulin overdose, where insulin excess prevents ketogenesis and leads to drowsiness, mood change and stress response (adrenergic symptoms).

In bulimia nervosa, and in the binge/purge form of anorexia nervosa and OSFED

- Most biochemical abnormalities are related to purging (i.e., self-induced vomiting and laxative abuse), which can lead to renal impairment

- Hypoglycaemia can also occur, possibly related to binge-related insulin surges

Creatine kinase

- CK is an enzyme contained in muscle cells and released when the muscle is damaged

- In eating disorders, the two most common causes of raised CK are muscle autophagy (i.e., the body metabolising muscle as a source of nutrition) and over-exercising, which can result in very high CK levels in undernourished patients who exercise

Micronutrients

- Vitamin deficiencies can give rise to abnormal blood tests For example:

- Vitamin C deficiency causing anaemia

- Low calcium and phosphate in vitamin D deficiency

Sex hormones

- In specialist services you may also need to check level of sex hormones

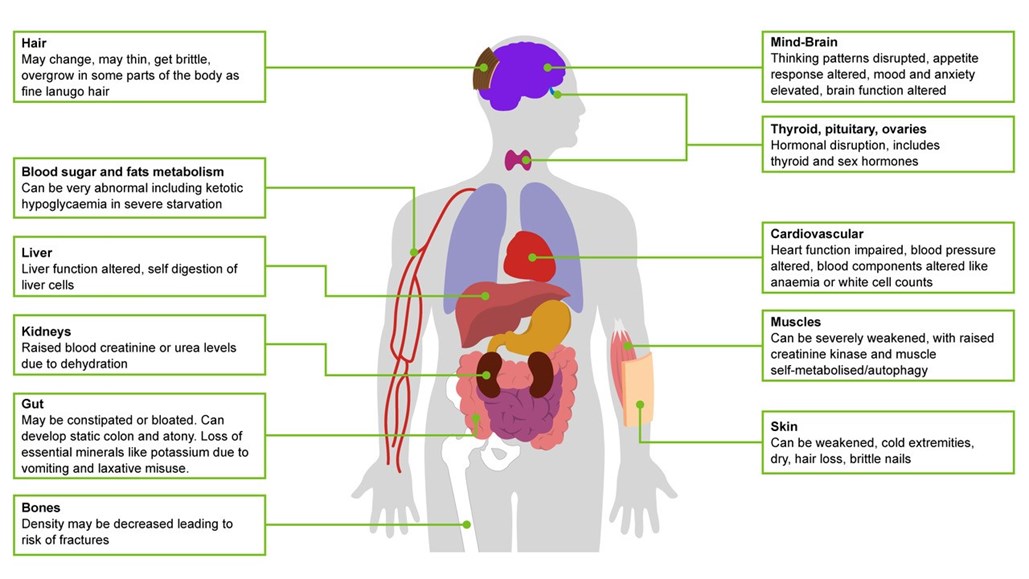

Look out for body symptoms of

- Dizziness

- Tiredness

- Muscle wasting and weakness

- Low body temperature (core temperature below 35oC)

- Cold hands and feet

- Dry skin

- Hair loss

- Re-emergence of downy unpigmented lanugo “baby” hair on the body

- Feeling faint and actually fainting

Young people who are vomiting should be encouraged to:

- have regular dental and medical reviews

- to very gently brush teeth after vomiting

- to rinse mouth with fluoride mouthwash after vomiting

- to briefly wait (15 minutes) before very gently brush teeth after vomiting

- and to avoid highly acidic foods and drinks

Young people who are exercising excessively should be advised to completely stop exercising in the first instance

- This is best advised after you have established a good initial engagement

Risk of low bone density is present for all young people who are severely underweight

- A bone density scan may be considered for all young women with secondary amenorrhea for longer than 12 months

- Seek advice from the paediatrician or an endocrinologist regarding optimal management of low bone density

Diabetes mellitus type 1

- Diabetes complicates the management of any eating disorder

- Insulin or hypoglycaemic drugs may be avoided by the patient to promote weight loss and this can lead to failure of diabetic control

- In the long term, increased severity of diabetic complications can occur. Psychiatrists and physicians must work closely together in order to optimise outcome in these complex clinical situations. Further info is available on the MEEDs resource and on the BEAT webpages, links in our resources section below

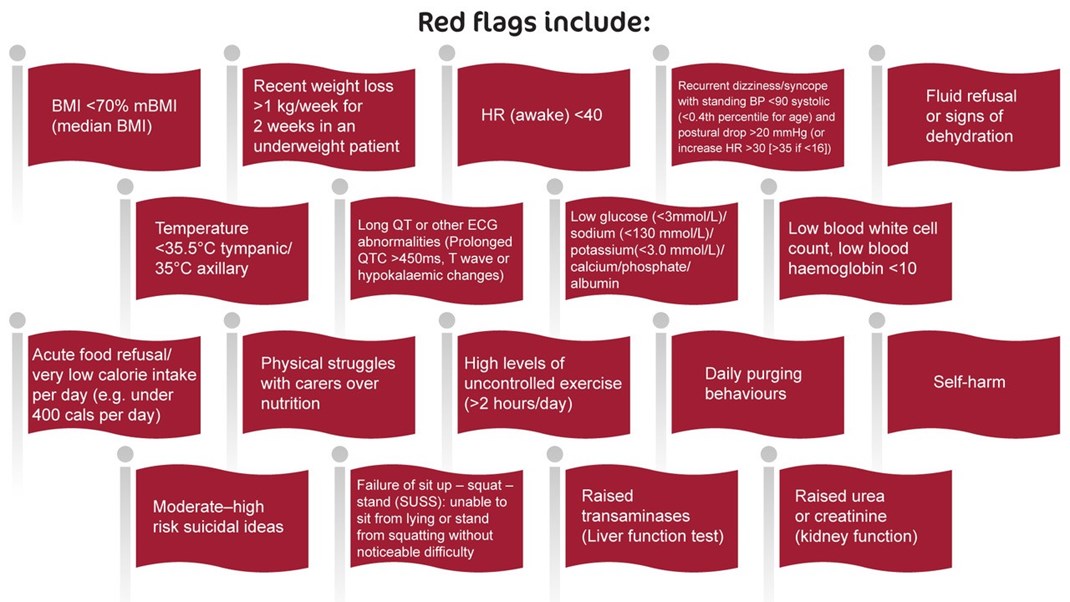

Red Flags in Primary Care

(summary courtesy of Medical Emergencies in Eating Disorders 2022 publication- please see MEEDS documents for more detail)

- Patients with eating disorders can appear well even when medically very unstable

- Consult the new Medical Emergencies in Eating Disorders (MEED, 2022) risk assessment framework checklist (see MEEDs resources) and use measures most relevant to the patient that you are assessing to decided is young person requires urgent medical admission

- Anyone with one or more ‘red rating’ (or several Amber ratings-for details please consult the MEED guidelines 2022) should probably be considered high risk, with a low threshold for admission to the medical/paediatric unit

When you identify multiple red alerts across physical domains, discuss referral to acute medical care

- This may include an emergency paediatric admission for medical stabilisation

- During stabilisation the young person will be treated for any severe electrolyte imbalance, dehydration or signs of incipient organ failure

Refeeding and ‘underfeeding’ syndromes: recognition, avoidance and management

- Refeeding syndrome is a rare, but a potentially fatal condition that occurs when patients whose food intake has been severely restricted are given nutrition via oral, enteral or parenteral routes

- Sudden reversal of prolonged starvation by the reintroduction of food leads to rapid shifts of electrolytes back into cells from which had, during starvation, been leached out from

- Phosphate, potassium and magnesium levels can fall very rapidly within the first week of refeeding, with neurological and cardiovascular consequences. This is known as the “refeeding syndrome”

- The resulting effects, most notably cardiac compromise, can be fatal.

- Respiratory failure, liver dysfunction, central nervous system abnormalities, myopathy and rhabdomyolysis are also recognised complications and patients are at risk for vitamin deficiencies.

- Refeeding syndrome usually occurs within 72 hours of beginning refeeding, with a range of 1–5 days, but bear in mind that it can occur late (in one study, up to 18 days) in the most malnourished

- There is a need to avoid underfeeding while also knowing how to monitor for signs of refeeding syndrome

Further Information

Resources

BEAT, HEE, RCPsych

- BEAT Tips Poster

- BEAT leaftlet: Seeking treatment for an eating disorder? The first step is a GP appointment.

- BEAT carers booklet: Eating disorders: a guide for friends and family

- Type 1 diabetes with an eating disorder: more information

- BEAT elearning for nurses (for all ages, not child and young person specific - Each of the 3 sessions will take around 30 to 60 minutes to complete and includes additional learning resources for those looking to further increase their knowledge. To access the elearning in the elfh Hub directly, please visit the links below.

Medical Emergencies in Eating Disorders (MEED)

- Medical Emergencies in Eating Disorders (MEED). Guidance on recognition and management. RCPsych College Report CR233, May 2022. (Replacing MARSIPAN and Junior MARSIPAN)

- Guidance on Recognising and Managing Medical Emergencies in Eating Disorders. Annexe 1: Summary sheets for assessing and managing patients with severe eating disorders. RCPsych College Report CR233, May 2022. (Replacing MARSIPAN and Junior MARSIPAN)

- Medical Emergencies in Eating Disorders. Annexe 2: What our National Survey found about local implementation of MARSIPAN recommendations. RCPsych College Report CR233, May 2022. (Replacing MARSIPAN and Junior MARSIPAN)

- Guidance on Recognising and Managing Medical Emergencies in Eating Disorders. Annexe 3: Type 1 diabetes and eating disorders (TIDE). RCPsych College Report CR233, May 2022. (Replacing MARSIPAN and Junior MARSIPAN)

NHSEI, NICE, NCCMH

- Eating Disorders: Recognition and Treatment NICE Guideline (NG69) 2020

- Access and Waiting Time Standard for Children and Young People with an Eating Disorder: Commissioning Guide, particularly in relation to managing transitions between services 2015

- Eating Disorders Quality Standard (QS175) 2018

- NHS England children and young people’s eating disorders programme 2019

Other useful resources

From MindEd session Eating Disorders: Further Information for Professionals:

- Talk ED

- Beat (beating eating disorders)

- Faculty of Eating Disorders Royal College of Psychiatrists

- F.E.A.S.T. (Families Empowered and Supporting Treatment of Eating Disorders)

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance for Eating disorders: recognition and treatment

- Maudsley Service Manual for Child and Adolescent Eating Disorders

References

- Bould H, De Stavola B, Lewis G, Micali N. Do disordered eating behaviours in girls vary by school characteristics? A UK cohort study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2018; 27: 1473–81.

- Byford S, Petkova H, Stuart R, Nicholls D, Simic M, Ford T, Macdonald G, Gowers S, Roberts S, Barrett B, Kelly J, Kelly G, Livingstone N, Joshi K, Smith H, Eisler I. Alternative community-based models of care for young people with anorexia nervosa: the CostED national surveillance study. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library; 2019.

- House J, Schmidt U, Craig M et al. Comparison of specialist and non-specialist care pathways for adolescents with anorexia nervosa and related eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 2012;45:949-956

- McClelland, J., Simic, M., Schmidt, U., Koskina, A., & Stewart, C. (2020). Defining and predicting service utilisation in young adulthood following childhood treatment of an eating disorder. BJPsych Open, 6(3), E37

- Neale J, Pais SMA, Nicholls D, Chapman S, Hudson LD. What Are the Effects of Restrictive Eating Disorders on Growth and Puberty and Are Effects Permanent? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.J Adolesc Health. 2019 Nov 23. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.08.032.

- NICE guideline (NG69) 2017. Eating Disorders; recognition and treatments.

- Nicholls D, Becker A. Food for Thought: Bringing Eating Disorders out of the shadows. BJPsych 2019 Jul 26:1-2.

- Petkova H, Ford T, Nicholls D, Stuart R, Livingstone N, Kelly G, Simic M, Eisler I, Gowers S, Macdonald G, Barrett B, Byford S. Incidence of anorexia nervosa in young people in the UK and Ireland: a national surveillance study. BMJ Open 2019; BMJ Open 2019 Oct 22;9(10)

- Simic, M., Stewart, C.S., Konstantellou, A. et al. From efficacy to effectiveness: child and adolescent eating disorder treatments in the real world (part 1)—treatment course and outcomes. J Eat Disord 10, 27 (2022)

- Stewart, C.S., Baudinet, J., Munuve, A. et al. From efficacy to effectiveness: child and adolescent eating disorder treatments in the real world (Part 2): 7-year follow-up. J Eat Disord 10, 14 (2022)

Further elearning from NHS HEE & MindEd

Children and Young People - MindEd resources

1) Eating Disorders in Young People

Description: For General Health CYP Entry Level Audience (5-18 yrs)

This session gives an overview of the nature, aetiology and risk factors linked to eating disorders. Also covered are the diagnostic elements that allow us to distinguish between eating disorders and other conditions affecting the eating behaviour of young people.

Author(s):

Dasha Nicholls

2) Eating Disorders; Anorexia and Bulimia

Description: For Specialist Mental Health CYP Health Entry Level Audience (5-18 yrs)

This session is aimed at more experienced/specialist users and outlines the diagnostic criteria and non-specific risk factors for eating disorders that most often start in childhood and adolescence. The eating disorders most frequently seen by mental health professionals, for example, anorexia nervosa, are explained in more detail. Treatment interventions and treatment outcomes for anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa will be discussed, with particular emphasis given to the key family therapy interventions for anorexia nervosa.

Author(s):

Mima Simic

Description: For wider general health audience (0-5 yrs olds)

This session describes the normal developmental progress of children from birth to five; from breast/bottle to eating independently and the difficulties encountered by parents during this developmental process.

Author(s):

Judy More

Description: For Families/parents/carers, Universal Audience (about CYP 5-18 yrs)

This session gives parents basic information and advice about the eating disorders: anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating and similar behaviour, that do not usually meet threshold criteria. It is not intended to address childhood obesity or infant eating difficulties.

Author(s):

Brian Jacobs

Mima Simic

5) Eating Disorders (CT): Families and Professionals

Description: Specialist CYP mental health entry level (5-18 yrs)

This session describes Community Eating Disorder Services for Children and Young people (CEDS-CYP) and the importance of accessing the right support for these disorders early. It explains the physical risks and psychological aspects of eating disorders and the multi-disciplinary nature of CEDS-CYP. It highlights the importance of engaging the young person in treatment and the role of the family in this. The session also outlines psychological and medical treatments, the need to attend to the often co-occurring psychiatric conditions and the use of medication.

Authors:

Mima Simic,

Rachel Bryant-Waugh

6) Eating Disorders (CT): Further Information for Professionals

Description: Specialist CYP mental health entry level (5-18 yrs)

This session will provide a background to Community Eating Disorder Services for Children and Young People (CEDS-CYP) and the assessment and treatment of eating disorders. It will cover psychological treatments, appropriate use of medication and co-occurring conditions.

Authors:

Mima Simic,

Rachel Bryant-Waugh

All ages - NHS HEE TEL Resources

Eating disorders training for health and care staff

This suite of training was developed in response to the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman (PHSO) investigation into avoidable deaths from eating disorders, as outlined in recommendations from the report titled Ignoring the Alarms: How NHS Eating Disorder Services Are Failing Patients(PHSO, 2017).

It is designed to ensure that health and care staff are trained to understand, identify and respond appropriately when faced with a patient with a possible eating disorder. It is the result of collaboration between eating disorder charity Beat and Health Education England with key partners.

Eating disorders training for medical students and foundation doctors

This eating disorders training is designed for medical students and foundation doctors. The two sessions will take around 20-30 minutes to complete and includes additional learning resources for those looking to further increase their knowledge. The sessions also provide good preparation for those who go on to participate in medical simulation training on eating disorders.

Eating disorders training for nurses

This eating disorders training is designed for the nursing workforce. Each of the 3 sessions will take around 30 to 60 minutes to complete and includes additional learning resources for those looking to further increase their knowledge.

Eating disorders training for GPs and Primary care workforce

This eating disorders learning package is designed for GPs and other Primary Care clinicians. The two sessions will take around 30-40 minutes each to complete and includes additional learning resources for those looking to further increase their knowledge.

- GPs and Primary Care: Understanding Eating Disorders

- GPs and Primary Care: Assessing for Eating Disorders

Medical Monitoring in Eating Disorders learning for all healthcare staff who are involved in the physical assessment and monitoring of eating disorders

The eating disorders learning package for Medical Monitoring is designed for primary care teams, eating disorder teams or other teams who are monitoring the physical parameters of a person with an eating disorder. The session will take around 30 minutes to complete and includes additional learning resources for those looking to further increase their knowledge.

Acknowledgements

These tips have been curated, drawn and adapted from a range of existing learning, including MindEd, NHSei, NICE, MMEEDs guidance, NHS HEE elfh/BEAT/RCPsych resources. Extracts from the MMEEDs are included with permission courtesy of the MMEEDs team.

The content has been edited by Dr Mima Simic (MindEd CYP Eating Disorders Editor) and Dr Raphael Kelvin (MindEd Consortium Clinical Lead) with close support of the inner expert group of Prof Ivan Eisler, Dr Dasha Nicholls, Dr Rachel Bryant Waugh and Dr Simon Chapman.

A wider expert reference groups include BEAT (Kathrina Dixon-Ward, Martha Williams, Brooke Sharp), Dr Elaine Lockhart (RCPsych Child and Adolescent Faculty Executive chair), Gemma Trainor (MindEd Consortium RCN lead rep), Prof Ulrike Schmidt (Professor SLAM/KCL and MindEd Editor) Dr Lisa Shostack (MindEd Consortium BPS Lead Rep).

Disclaimer

This document provides general information and discussions about health and related subjects. The information and other content provided in this document, or in any linked materials, are not intended and should not be construed as medical advice, nor is the information a substitute for professional medical expertise or treatment.

If you or any other person has a medical concern, you should consult with your healthcare provider or seek other professional medical treatment. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something that you have read in this document or in any linked materials. If you think you may have an emergency, call an appropriate source of help and support such as your doctor or emergency services immediately.

MindEd is created by a group of organisations and is funded by NHS England, the Department of Health and Social Care and the Department for Education.

© 2023 NHS England, MindEd Programme