Dealing with Stress & Trauma in Education Settings

Created in partnership with Education Support

Created in partnership with Education Support

Introduction

This set of tips from our international panel of healthcare and education experts adapted for education staff are intended to help:

- All staff to better manage stress and distress

- Support wellbeing, and build psychosocial resilience

- Reduce risk of burn-out

- Support staff who may have experienced trauma

There are two main sections: ‘things to do’ and ‘things to know’. Use this resource as works for you. The headline tips give rapid access advice and the drop-downs beneath each tip provide more detail.

Pressure and daily hassles are a normal part of life. For some of us, repeated or accumulated stress can affect the way we live our lives and our ability to carry out our role in an education setting. For others, it may be that stress can bring back feelings related to trauma earlier in our lives, and this can be difficult to manage by ourselves.

There will be times when we witness a traumatic event at work, which can impact on our mental health. Unfortunately, some of us will experience trauma directly during our working life as well.

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought new and different challenges, and many education staff have felt increased stress. Some have experienced trauma as a result of this.

Education staff often show tremendous resilience to stress. Making a record of what you do when you cope well with stress can be really helpful. You can look back at that record in times when stress is making you feel low.

Remember, simple things can make a huge difference.

Sleep, eat, turn off (including online), seek social support and keep daily rhythms.

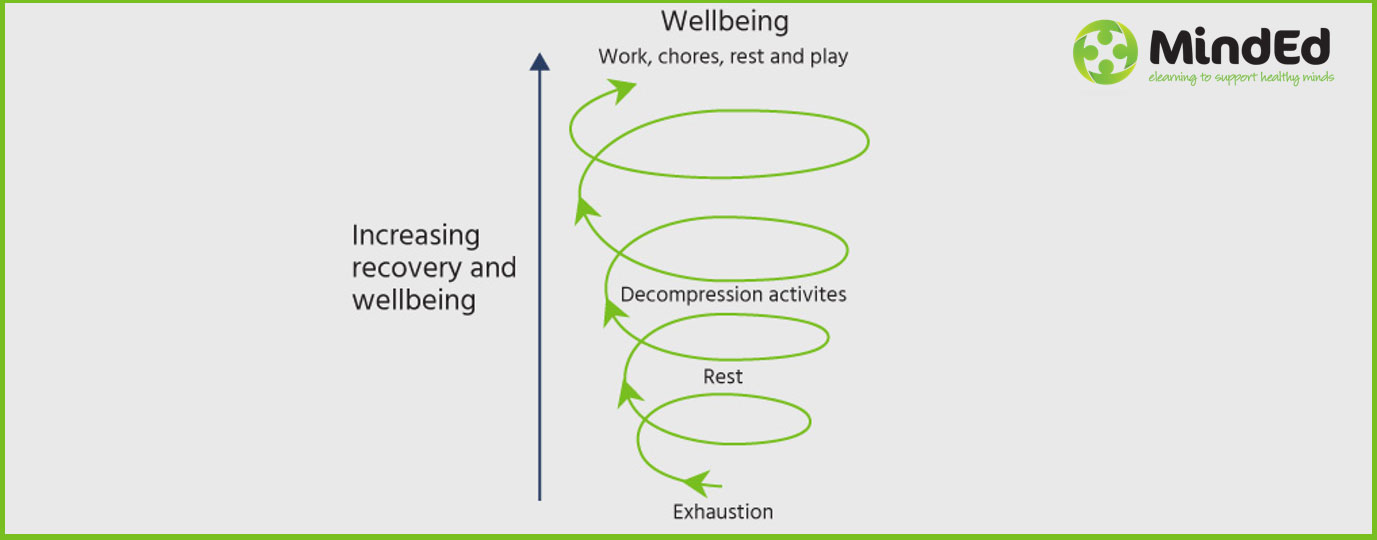

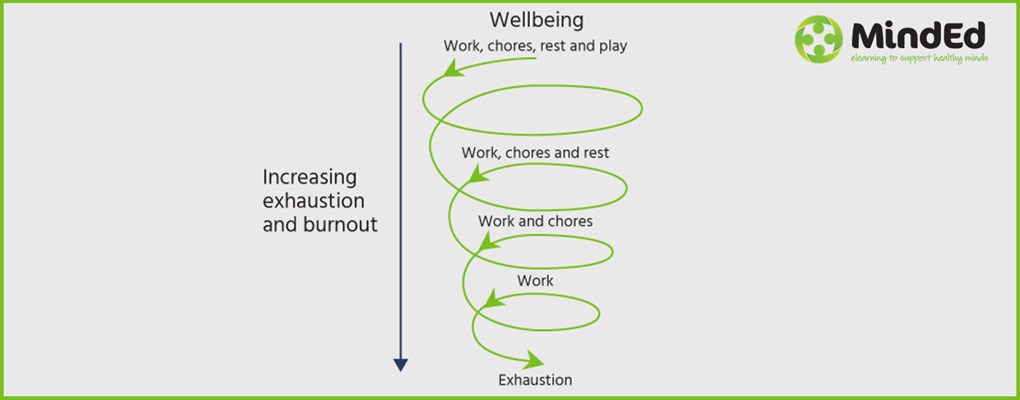

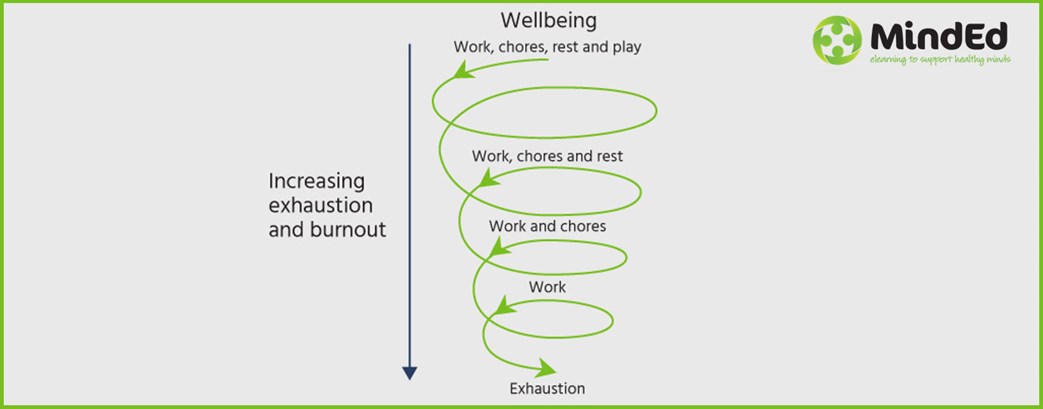

Remember your own needs. The following graphic provides a summary of a virtuous cycle of recovery and wellbeing from exhaustion, and by implication shows the downward spiral that can occur leading to exhaustion and burnout. This will be illustrated later on in this tip sheet.

Things to do

Do

![]()

Daily routines: get up at a regular time, make sure you sleep in the dark, eat regularly, prepare healthy food - give this enough time, keep hydrated with water, exercise for social, physical and mental benefits, use breathing exercises and yoga. The NHS have compiled a list of recommended resources to help you keep a daily routine.

Protect your sleep. You can access 'Sleepio' through the NHS Help website

Remember: It is a marathon, not a sprint. This (crisis) too will pass

![]()

Keep in regular contact with relatives and friends, and or community, this may be local or much more distant. The internet can really help these days

![]()

Let your imagination run free; imagine how life will be once it returns to normal. This may be a challenge in present circumstances, but it can be helpful

Focus on the things you can control

Do the things you’ve done before that relax you, for example spending time with friends and family, cooking, physical activity etc.

Rejuvenate yourself: hobbies, listening to music, films, TV, reading, podcasts, poetry, jigsaws

![]()

Do activities that utilise your skills, your empathy and kindness. Support a charity, faith or community group, or walk a neighbour’s dog. Even an hour a week is welcomed and helps others, as you help yourself.

Don't

- Don’t let yourself use unhelpful ‘supports’ such as smoking, gambling, drugs, alcohol. At the very least have alcohol free days and seek alternative healthy supports

- Don't work without breaks

- Don’t be afraid to admit your fears, to yourself and when appropriate, to others

- Don’t fall asleep whenever: try to maintain good sleep routines, take time to find a quiet dark space where you can properly sleep and not just nap

- Don’t be harsh on yourself – it won’t help you or anyone else

Make plans for ‘you-time’ – do something you enjoy doing, it helps relieve pressure and calms arousal

![]()

Unpressured exercise, such as walking, cycling or team sports, can help you feel good in lots of ways. It is easy to feel guilty if we don’t exercise, so choose an aspect you enjoy and make time to do it. If you like the feeling you get from physical engagement keep enjoying it and gently encourage others to join in. It can help socially, physically and mentally

![]()

Step away from social media if it makes you feel anxious and report any harmful interactions

Avoid dwelling on, or constantly checking the news - limit your digital updates and notifications to certain times and trusted sources

![]()

Plan time for friends, family and community. It is too easy for work to blend into your family, personal or leisure time. Give yourself some rules such as ‘no phones at the meal table’ to give priority to relationships

![]()

Be your own cheerleader. When we are feeling anxious, we typically underestimate our ability to cope, and forget what did in the past that worked for us, while over-estimating the risk

![]()

Run a club or give some time to local charities, communities or networks. Not everyone responds well to doing nothing as a form of relaxing, but it is important for some. Respect each other’s choices about ways to relax

Support yourself with helpful self-talk

![]()

'It’s OK to need a rest or break. It’s not selfish'

![]()

'I mustn’t work around the clock. Aside from everything else, it makes me less effective for the children’

![]()

‘Thank you for being there for me last week. I feel so much better’

![]()

‘I know better now how to spot the signs of too much stress. I will listen to others when they spot it in me too’

![]()

‘To help others, I also need to look after myself’

If you start feeling in crisis, make sure to pause, however briefly

![]()

You may have feelings of panic, notice that everything around you seems unreal, or have unusual sensations such as an out-of-body experience. These are well-recognised but temporary reactions to overwhelming stress. There are many strategies, but many people find simple ‘grounding’ techniques help. Use breathing and linked counting techniques (see resources for links)

![]()

If it’s too much, ask to leave the immediate situation and take a bit of time out – that’s really OK. It is a sign of strength to be able to look after your needs

![]()

Be open to offers of help. You are human and you deserve help too

![]()

You may be able to re-focus on the work task while also looking after your mind. Remember the things you have learned before to help you when you’re stressed (and the ones to avoid)

![]()

When you better understand your own feelings and responses to a crisis, model this to others through your open body language to generate calm in the space; shoulders down, soft facial features, open palms etc.

It's ok not to be ok - you may feel overwhelmed, shocked and numb, at times

![]()

It can help to accept your emotions as they are, and let them go through you as a wave so that your body doesn’t fight your mind for a while – it is best not to use this as your only strategy

![]()

Consider if there is a specific thought or action you need to deal with and take it from there. This may mean you need support from your work buddy or your line manager. You may also need support from friends and family. If you still feel distressed, you may need additional support. Consider contacting the Education Support helpline

You may have access to an employee assistance provider. If this information is not easily available within your setting, check with your Human Resources/Personnel department. A list of employee assistance providers in the UK can be found here. Alternatively for settings without an HR department seek support from your School Business Leader, Governors or Local Authority as other potential sources of assistance

To see what Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) are available in your area, click here. By putting in your postcode you can see what services are available, including iTalk, and which services have self-referral

![]()

Support groups for those with similar experiences may be helpful

It’s good to be part of a team or social group that allows you space and compassion to not feel okay. But is one that provides you with secure, uncritical boundaries to let you know when your ‘not being ok’ is impacting on those around you

![]()

Learn to recognise and better understand your triggers, or the things that can make you wobble, so that you can begin to build self-protecting strategies

Keeping a reflective keyword or visual diary may help with this process

![]()

Sharing your own personal experiences may help others, but be sensitive to the impact on the other person

Do not leave yourself alone with uncomfortable feelings

![]()

If you have a pre-existing mental health condition and are already receiving treatment, remember to also keep in touch with your mental health worker or team, and don’t stop any prescribed medication without advice

![]()

Use your buddy, team leader or another trusted person to share anxiety, fears, grief, etc. See our section on Tips for Supporting Each Other

![]()

Use your personal, religious or community networks if they are a trusted source of support for you

![]()

Make use of regular supervision, if available. If supervision is not provided in your setting, seek training or build knowledge with a colleague to explore ways of providing each other with peer supervision

Learn the ways in which you manage your feelings when you are in a positive emotional space, so that you can draw on these strategies when you are stressed

![]()

If you find a process that works well for you, explore ways to share this with the whole school team. See our Tips for Managers and Team Leaders

Kindness and good humour are age-old antidotes to stress for you and the team

![]()

Choose kindness for yourself as well as others

![]()

Good humour is always kind and never harmful to others. Beware of sarcastic or sardonic humour in the workplace. Gallows humour is often said to be a survival strategy but is rarely supportive

![]()

Kindness and or good humour ripple across the team

![]()

Consciously spot the positives in each day, for yourself and others; for example, make a note of three things that you are grateful for, that went well for you, and why, as you get ready to go to bed, this helps reset balance of thinking towards gratitude and hopefulness

![]()

Allow time and remind each other to imagine, reflect, express, let go, create, laugh, cry, have fun

Plan and make use of regular communication in the team

![]()

Good team working and communication across the team helps reduce stress and the physiological effects of stress on our bodies. See our section on Tips for Managers and Team Leaders

![]()

Draft any written communication about something you feel strongly about first and delay send – emails written in haste or when you are cross are rarely helpful in the long run

![]()

Agree times for communication that work for everyone within the team. These might be different for different groups – you may prefer to liaise with your year team colleague when you have space to plan, but don’t want management emails about monitoring at that time. It is okay to state your preferences

Have a ‘work buddy’ – but agree boundaries for this relationship. A relationship in which one of you moans all the time and the other just listens is not helpful to either

![]()

Communicate the positives to each other. If you are pleased with something a child has achieved, share that with others. We often feel embarrassed about promoting ourselves, but if it is done to share good practice and not done just to seek praise from others, it will be well received and hopefully encourage more people to do the same

![]()

Make a note of when communication works well and feed this back into school policy and practice. You may want to do this through an intermediary, such as a staff governor

After an immediate crisis, take time to 'decompress' in a team - like a diver after a deep dive

![]()

Be aware of your own body and avoid the false sense of feeling of okay soon after a traumatic event or crisis. Adrenalin can trick you into thinking your body is ready to go again but take time to rest and recover. It is natural for tears or low feelings to overcome us, as our bodies crash after a false ‘okay’. You will feel better again soon

![]()

Finding ways to talk regularly with a buddy or with your team at the beginning and end of a school day can be very helpful. Talk about the tasks to be done, and afterwards discuss what has gone well and what has been challenging or demoralising

![]()

Regular, team-based ‘operational debriefing/decompression’ in a supportive reflective context is helpful to team learning, morale, and each member’s wellbeing

![]()

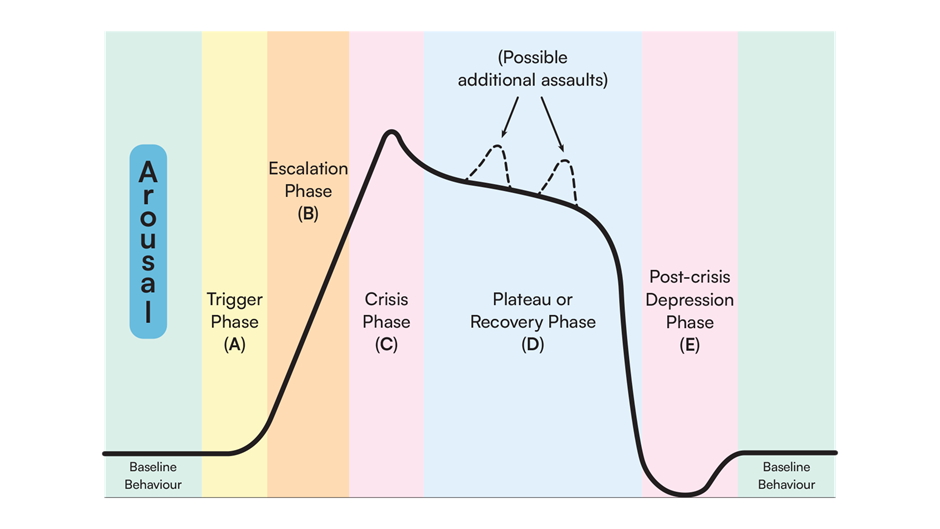

Learn about the ‘escalation’ (arousal-assault) cycle so that you can better understand your own responses to a violent or traumatic event and recognise it in children and young people, and your colleagues

Adults working with children or young people going through an assault cycle, can often find their own emotions playing out in a similar pattern, slightly behind the child. Being aware helps us to prepare.

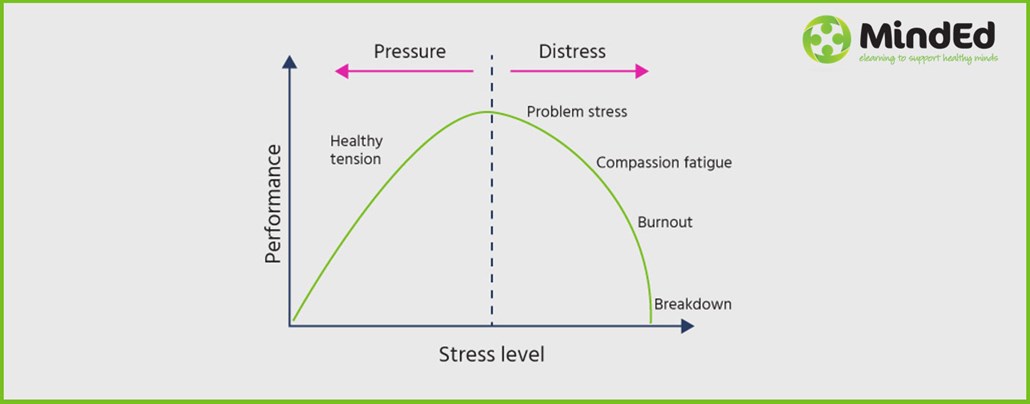

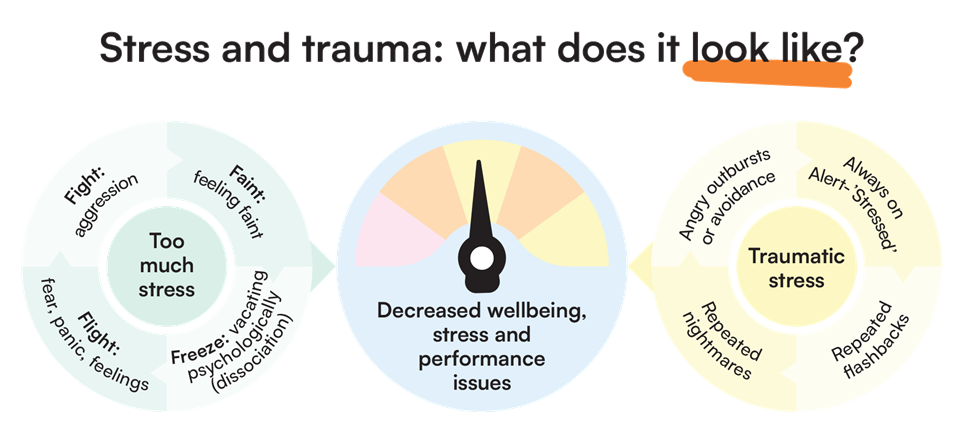

This is similar to the Yerkes-Dodson model which helps us understand that some pressure/stress is normal, it is when we go over the top of the curve, that problems develop, and things feel overwhelming

![]()

Support others to take time in their ‘decompression chamber’. This may mean taking their class for a while or getting someone to take your class for a while so you can sit quietly alongside a colleague in the staffroom

As a team, avoid one-off psychological debriefing sessions. They have been found to be unhelpful

![]()

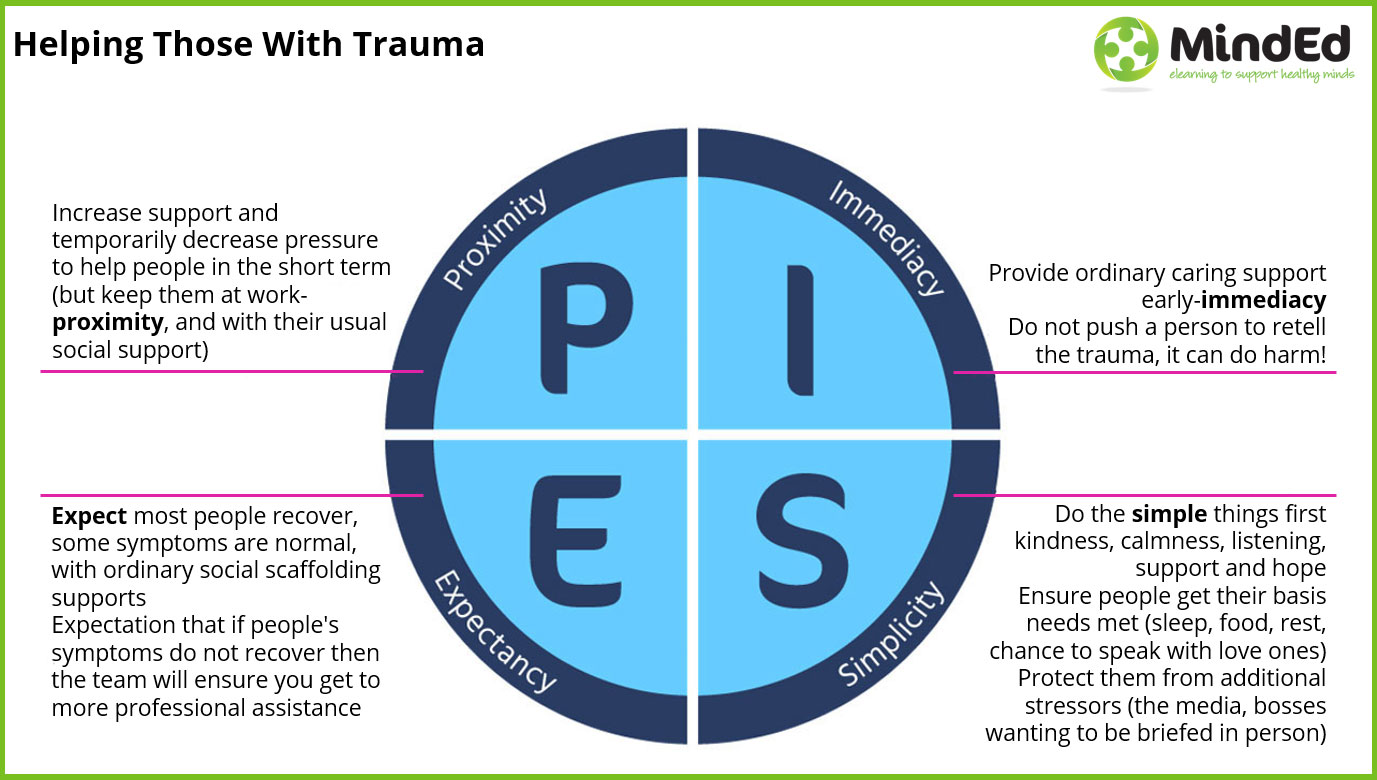

Intrusive, albeit well-meaning, attempts to make people relive a traumatic incident immediately afterwards, usually by somebody outside the team itself, can increase the risk of later PTSD; it can be overwhelming

![]()

It is essential that people do not feel obliged to share or describe experiences if they do not want to do so

![]()

‘Being there’ for each other. Being a fellow human being is enough- don’t feel you need to do something clever or special. You can just be a quiet physical presence, or something as simple as a text to say you are thinking of someone. Simple but so important. Sharing the person’s experience in detail is not a condition of support

![]()

Build your skills for reflective practice and empathetic support

![]()

If your setting doesn’t provide training to develop these skills, take time to skill yourself – being on this website is already the first step!

Things to know

What is trauma

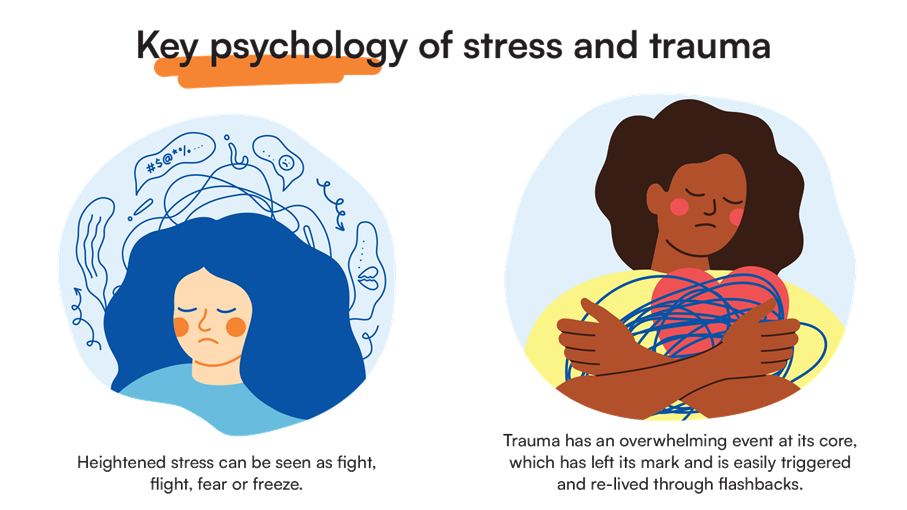

Psychological trauma is better recognised now than it was in the past. We are all different, and cope differently with events but we can support one another, and this really helps. The following slide highlights body responses that underlie stress and the link between overwhelming stress and psychological trauma.

In educational settings, staff may have to manage many difficult situations which trigger emotional responses. Unlike many frontline staff, there are not always the same support systems in place, such as professional supervision. In delivering your role you may have to manage your own responses, and supervision can really help. Especially when children disclose abuse, violent or critical incidents, life-limiting illnesses, serious physical injury or even death. There is further training available for reflective supervision in schools. The following slide provides more learning on the psychobiology of stress and trauma responses.

Some warning signs that a person may need extra help, or even urgent help

- Several weeks of sadness or depression, with a reduced interest in daily activities. This may vary during the day; there may even be moments of pleasure and joy, but the main mood is sadness

- Withdrawal from friends

- Self-harm and suicidal thoughts or actions (urgent help should be sought)

- Lack of sleep, loss of appetite, or development of a prolonged fear of being alone

- A sharp drop in work performance

- Self-neglect

- Refusal to believe that the person has died or that the event happened

- Repeated flashbacks, getting panicky following a trauma

- Difficulties become worse or new troubles persist after several weeks

Some warning signs you may be burning out, or overstressed yourself

- Working 'round the clock' and feeling that you are not doing enough

- Feeling guilty / blaming yourself / going over and over in your mind about what you could have done differently

- Work constantly creeping into your leisure and family time, because it feels easier to let yourself, or your family down than feel you’re not performing well in your job

- Using an excess of sugar and caffeine

- Becoming hyper-vigilant: extremely sensitive or critical of others who don’t ‘do things your way’ – this may be a sign of critical stress

Remember: during times of extreme stress all our good and bad coping habits tend to become exaggerated

The “burnout” diagram illustrates the importance of intervening early

Work together as a team to help each other stay as close as possible to the balanced “wellbeing” end of the spiral, look out for yourself and each other if you notice signs of burnout

After a while

- Most people recover from distressing and traumatic experiences without specialist input, but that doesn’t mean the process isn’t painful

- It can take time. Some people need extra help to recover. This is not a sign of weakness – it can sometimes be the most conscientious, hard-working and responsible people who are hardest hit

- If things aren’t getting any better for you, talk first to family and friends or other community support. Consider contacting Education Support. Your school may have an Employee Assistance Programme that offers helpful support. If you can, discuss how you are feeling with a colleague, line manager or a member of the senior leadership team. You may feel that you need support from your GP for professional advice. You may want to consult formal psychological support services like IAPT– you can self-refer. Remember your psychological health is just as important as your physical health

- We tend to search for meaning after a traumatic or highly stressful life event. We try to work out why the event happened. Blaming somebody else, ourselves, or feeling guilty, is mostly wrong and nearly always unhelpful in getting over these experiences. However, it is often difficult to deal with these feelings on our own

- It can be helpful to say to yourself or to a colleague, 'it was not your fault', 'This happened to you, not because of you', 'you did everything you could, most people would have done the same'; or 'you would never be this hard on anyone else'. This can help to counter the tendency towards guilt and self-blame

- You may want, and need a longer, more thorough psychological intervention, particularly after the crisis has passed. Do ask. You deserve it. Calling a helpline, such as the Education Support Helpline can be a first step for some, and you can always call Samaritans at any time. Your leadership team, Occupational Health, or your GP should also be able to direct you to further support

If a colleague wants to tell you about a trauma

- Accept and validate thoughts and feelings

- Avoid pointed questions that cause re-living of traumas. It is ok to focus on what is happening now, what has become difficult and what has helped in the past

- Sometimes trying to forget and move on is exactly right

- We are all different so how, when and where each of us recollects and processes what they went through is unique

- Quash your own curiosity. Allow the person space to talk, rather than asking questions that are aimed at giving you more information

- No one-off solution will solve stress or trauma reactions

- NOTE: if a child wants to speak about a trauma, the approach would be different and need to include standard safeguarding and confidentiality related considerations

Resources

Education focused external resources

- Education Support helpline

- 08000-562-561

- Education Support Website

- Education Support teachers hub

- Mentally Healthy Schools whole-school approaches to staff wellbeing

Reflective conversations and professional supervision

- Education Support elearning on reflective conversations in education settings

- Talking Heads Supervision Ltd – Supervision Curious

- Barnardos - Supervision in Education - Healthier Schools for All

- Report drawing on research in schools in Scotland and across the UK

- Charlie Waller Trust – advice on supervision

-

EdPsy.org.uk – blog on the role Educational Psychologists can play in supervision

For children and young people affected by loss and death

- Anna Freud Centre - Bereavement and Loss

- Child Bereavement UK Specific information for the education sector, including a live chat Monday – Friday 9.00-5.00 and a Helpline 0800 02 888 40

- Child Bereavement UK and London Grid for Learning Managing a Sudden Death in the Community

- Cruse- variety of leaflets which may be helpful, including in Welsh language

- Government of Wales national framework for bereavement care

- Manchester Resilience Hub

- MindEd Mindfulness e-learning session

- National Suicide Prevention resources

- Winston's Wish - free online bereavement training accessible without charge after registration

- Young Minds - Grief and Loss

Acknowledgements

The content for these tips was written and edited by Dr Raphael Kelvin and Dr Julie Greer. They draw upon the suite of tips on the MindEd Hub and input from our reference groups of healthcare and education setting experts, to whom we are most grateful.

Education Reference Group: John Dexter, John Ivens, Margaret Mulholland, Steve Rippin, Jason Turner

Wider Stakeholder Group: Sinéad Mc Brearty, Faye McGuinness, Joanna Holmes, Lisa Shostack, Mina Fazel, Andy Bell, Ray McMorrow, Sarah Hannifan, James Brown, DFE (Emma Woodshaw), Sarah Lyons, Steve Cooper

© 2022 Education Support Limited, MindEd / Royal College of Psychiatrists and Health Education

Disclaimer

This document provides general information and discussions about health and related subjects. The information and other content provided in this document, or in any linked materials, are not intended and should not be construed as medical advice, nor is the information a substitute for professional medical expertise or treatment.

If you or any other person has a medical concern, you should consult with your healthcare provider or seek other professional medical treatment. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something that you have read in this document or in any linked materials. If you think you may have an emergency, call an appropriate source of help and support such as your doctor or emergency services immediately.

MindEd is created by a group of organisations and is funded by NHS England, the Department of Health and Social Care and the Department for Education.

© 2023 NHS England, MindEd Programme